I am re-posting this information which is from Wikipedia. I have not written one word of this blog, but I think it is important enough to post. The President of the USA may now be using this tactic with IRAN. It has been used before and Americans will fall prey to it again unless people are aware of the tactic and stand up to it.

Estoy re-publicando esta información que es de Wikipedia. No he escrito una palabra de este blog, pero creo que es lo suficientemente importante como para publicar. El presidente de los EE. UU. Ahora puede estar usando esta táctica con IRAN. Se ha usado antes y los estadounidenses volverán a ser presa de él a menos que la gente esté consciente de la táctica y la haga frente.

我正在重新發布來自維基百科的這些信息。 我沒有寫過這個博客的一個詞,但我認為發布這個詞非常重要。 美國總統現在可能正在與伊朗使用這種策略。 它已經被使用過了,除非人們意識到這種策略並且能夠堅持下去,否則美國人將再次成為它的犧牲品。

Ich poste diese Informationen, die aus Wikipedia stammen, erneut. Ich habe kein Wort dieses Blogs geschrieben, aber ich denke, es ist wichtig genug, um etwas zu posten. Der Präsident der USA könnte diese Taktik jetzt mit dem IRAN anwenden. Es wurde schon früher benutzt und die Amerikaner werden wieder Opfer davon werden, es sei denn, die Leute sind sich der Taktik bewusst und halten sich dagegen.

Rally ’round the flag effect

Jump to navigationJump to search

The rally ’round the flag effect (or syndrome) is a concept used in political science and international relations to explain increased short-run popular support of the President of the United States during periods of international crisis or war.[1]Because rally ’round The Flag effect can reduce criticism of governmental policies, it can be seen as a factor of diversionary foreign policy.[1]

Contents

Mueller’s definition[edit]

Political scientist John Mueller suggested the effect in 1970, in a landmark paper called “Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson”. He defined it as coming from an event with three qualities:[2]

- “Is international”

- “Involves the United States and particularly the President directly”

- “Specific, dramatic, and sharply focused”

Causes and durations[edit]

Since Mueller’s original theories, two schools of thought have emerged to explain the causes of the effect. The first, “The Patriotism School of Thought” holds that in times of crisis, the American public sees the President as the embodiment of national unity. The second, “The Opinion Leadership School” believes that the rally emerges from a lack of criticism from members of the opposition party, most often in the United States Congress. If opposition party members appear to support the president, the media has no conflict to report, thus it appears to the public that all is well with the performance of the president.[4]

The two theories have both been criticized, but it is generally accepted that the Patriotism School of thought is better to explain causes of rallies, while the Opinion Leadership School of thought is better to explain duration of rallies.[3] It is also believed that the lower the presidential approval rating before the crisis, the larger the increase will be in terms of percentage points because it leaves the president more room for improvement. For example, Franklin Roosevelt only had a 12% increase in approval from 72% to 84% following the Attack on Pearl Harbor, whereas George W. Bush had a 39% increase from 51% to 90% following the September 11 attacks.[5]

Another theory about the cause of the effect is believed to be embedded in the US Constitution. Unlike in other countries, the constitution makes the President both head of government and head of state. Because of this, the president receives a temporary boost in popularity because his Head of State role gives him symbolic importance to the American people. However, as time goes on his duties as Head of Government require partisan decisions that polarize opposition parties and diminish popularity. This theory falls in line more with the Opinion Leadership School.

Due to the highly statistical nature of presidential polls, University of Alabama political scientist John O’Neal has approached the study of rally ’round the flag using mathematics. O’Neal has postulated that the Opinion Leadership School is the more accurate of the two using mathematical equations. These equations are based on quantified factors such as the number of headlines from the New York Times about the crisis, the presence of bipartisan support or hostility, and prior popularity of the president.[6]

Political Scientist from The University of California Los Angeles, Matthew A. Baum found that the source of a rally ’round the flag effect is from independents and members of the opposition party shifting their support behind the President after the rallying effect. Baum also found that when the country is more divided or in a worse economic state then the rally effect is larger. This is because more people who are against the president before the rallying event switch to support him afterwards. When the country is divided before the rallying event there is a higher potential increase in support for the President after the rallying event.[7]

In a study by Political Scientist Terrence L. Chapman and Dan Reiter, rallies in Presidential approval ratings were found to be bigger when there was U.N. Security Council supported Militarized interstate disputes (MIDs). Having U.N. Security Council support was found to increase the rally effect in presidential approval by 8 to 9 points compared to when there wasn’t U.N. Security Council support.[5]

According to a 2019 study of ten countries in the period 1990-2014, there is evidence of a rally-around-the-flag effect early on in an intervention with casualties (in at least the first year) but voters begin to punish the governing parties after 4.5 years.[8]

Historical examples[edit]

The effect has been examined within the context of nearly every major foreign policy crisis since World War II. Some notable examples:

- Cuban Missile Crisis: According to Gallup polls, President John F. Kennedy‘s approval rating in early October 1962 was at 61%. By November, after the crisis had passed, Kennedy’s approval rose to 74%. The spike in approval peaked in December 1962 at 76%. Kennedy’s approval rating slowly decreased again until it reached the pre-crisis level of 61% in June 1963.[3][9]

- Iran hostage crisis: According to Gallup polls, President Jimmy Carter quickly gained 26 percentage points, jumping from 32 to 58% approval following the initial seizure of the U.S. embassy in Tehran in November 1979. However, Carter’s handling of the crisis caused popular support to decrease, and by November 1980 Carter had returned to his pre-crisis approval rating.[10]

- Operation Desert Storm (Persian Gulf War): According to Gallup polls, President George H. W. Bush was rated at 59% approval in January 1991, but following the success of Operation Desert Storm, Bush enjoyed a peak 89% approval rating in February 1991. From there, Bush’s approval rating slowly decreased, reaching the pre-crisis level of 61% in October 1991.[3][11]

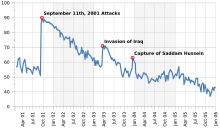

- Following the September 11 attacks in 2001, President George W. Bush received an unprecedented increase in his approval rating. On September 10, Bush had a Gallup Poll rating of 51%. By September 15, his approval rate had increased by 34 percentage points to 85%. Just a week later, Bush was at 90%, the highest presidential approval rating ever. Over a year after the attacks occurred, Bush still received higher approval than he did before 9/11 (68% in November 2002). Both the size and duration of Bush’s popularity after 9/11 are believed to be the largest of any post-crisis boost. Many people believe that this popularity gave Bush a mandate and eventually the political leverage to begin the War in Iraq.[3][12]

- Death of Osama bin Laden: According to Gallup polls, President Barack Obama received a 6% jump in his Presidential approving ratings, jumping from 46% in the three days before the mission (April 29 – May 1) to a 52% in the 3 days after the mission (May 2–4).[13] The rally effect didn’t last long, as Obama’s approval ratings were back down to 46% by June 30.

Controversy and Fears of Misuse[edit]

There are fears that the president will misuse the rally ’round the flag effect. These fears come from the “diversionary theory of war” in which the President creates an international crisis in order to distract from domestic affairs and to increase their approval ratings through a rally ’round the flag effect. The fear associated with this theory is that a President can create international crisis to avoid dealing with serious domestic issues or to increase their approval rating when it begins to drop.[14]

“Of course the people don’t want war. But after all, it’s the leaders of the country who determine the policy, and it’s always a simple matter to drag the people along whether it’s a democracy, a fascist dictatorship, or a parliament, or a communist dictatorship. Voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism, and exposing the country to greater danger.” — Herman Goering at the Nuremberg trials

Jun 19, 2019 @ 21:34:45

This would be a diversionary war with Iran, suitable to make the people forget Chump’s problems at home.It also serves to bring his allies/former allies into line since he threatens the end of trade with the US or US companies abroad to anyone who defies him and supports Iran. I plead with the UK to do the honourable thing and support Iran and not war. Chump appears to disregard the likelihood of body bags containing the youth of America turning up and causing parents to question this war.

Hugs

LikeLike