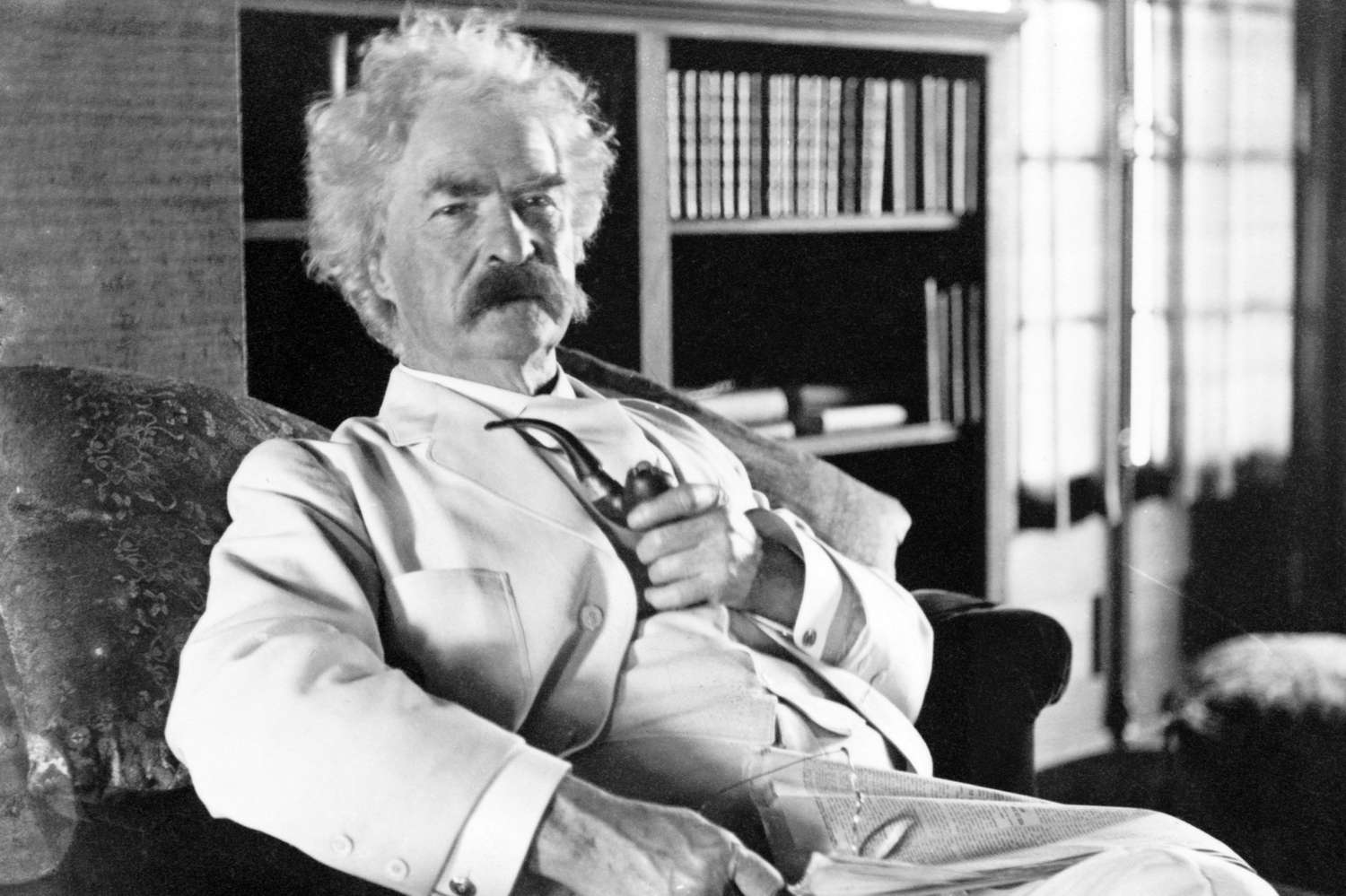

This imagined conversation reflects questions I’ve been asking myself about writing, purpose, and voice. If you’re a fellow blogger or lifelong learner, I hope some of these reflections resonate with you as much as they did with me. My two favorite writers growing up were Dostoevsky and Mark Twain. I knew I could never write as well as Dostoevsky, but I had dreams or maybe delusions of being another Mark Twain. Whenever I write, he is in the back of my mind. Here is a discussion that took place between Mr. Twain and I on his front porch with a little help from Metis, my AI assistant. She has an excellent knack for understanding Twain and for speaking frankly in his voice.

Setting:

A wide wooden porch overlooking the Mississippi. Late afternoon. Cicadas humming. Two rocking chairs. A battered notebook on a small table. A riverboat whistle in the distance.

Present:

John Persico and Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens)

Twain (leaning back, cigar unlit, eyes amused):

Well now, John, I must say—any man who invites a dead author for a conversation is either a philosopher… or dangerously optimistic.

John (smiling):

Probably a bit of both, Mr. Twain. I’ve been talking to long-dead thinkers for years. You’re in good company.

Twain:

That explains the thoughtful look. Most men your age are arguing with their televisions.

Now… you’ve summoned me. That means you want something. Confession, compliment, or correction?

John:

All three, if possible. You’ve always been my writing hero. I’ve tried to write honestly, critically, and with humor—but sometimes I wonder if I’m wandering too far into lectures instead of stories.

Twain (laughs):

Ah. The ancient disease of intelligent men: explaining things too well.

Let me ask you first—why do you write?

John:

To make sense of the world. To challenge foolishness. To honor people who don’t get heard. To leave something behind that isn’t just noise.

Twain:

Good. That’s four better reasons than most writers ever manage.

But let me tell you something uncomfortable:

Readers do not come to be improved.

They come to be entertained.

They are improved accidentally.

John:

That sounds like something you’d say.

Twain:

It is. And I’m proud of it.

Now—your writing. I’ve been… peeking.

(He taps the notebook.)

You think deeply. You connect history, politics, systems, morals, economics, technology. You’ve got a mind that builds bridges between ideas. That’s rare.

But sometimes—

you march your reader across those bridges like a drill sergeant.

John (laughs):

Guilty.

Twain:

You say, “Follow me. This matters.”

I preferred to say, “Come look at this ridiculous thing—oh my, would you look at that—good heavens, now we’re trapped in truth.”

John:

You smuggled ideas inside stories.

Twain:

Like whiskey in a medicine bottle.

Your essays are strong. Your arguments are strong. Your ethics are strong.

But your secret weapon is not your intelligence.

It’s your life.

John:

My life?

Twain:

You’ve counseled workers. Taught students. Worked in systems. Served in the military. Aged thoughtfully. Loved. Failed. Loved again. Adjusted. Tried again. Lived through several epochs in Americas.

And yet sometimes you write as if you’re afraid your own story and history isn’t enough.

It is.

John (quietly):

I’ve always wondered if personal writing was… self-indulgent.

Twain:

Only when it’s dishonest.

Honest personal writing is public service.

When you tell how you struggled with technology, power, aging, ethics—

you give permission for others to admit they’re struggling too.

That’s literature.

John:

So… more stories?

Twain:

More scenes.

Let me show you.

Instead of:

“Modern systems dehumanize people.”

Try:

“I once sat across from a man who had been fired by a computer. He wasn’t angry at the company. He was angry at the screen.”

See the difference?

John:

One makes you feel it.

Twain:

Exactly. Feelings sneak past defenses. Arguments set off alarms.

Now—your subjects. Veterans. Democracy. AI. Economics. Ethics. Power.

Heavy freight.

You’re hauling pianos uphill.

Why?

John:

Because no one else seems willing to.

Twain:

True.

But here’s the trick:

Whistle while you push.

Humor is not decoration.

It’s leverage.

When people laugh, they open their mouths. That’s when you feed them truth.

John:

Sometimes I worry humor makes things seem less serious.

Twain:

Nonsense.

Nothing exposes hypocrisy faster than laughter.

A tyrant fears comedians more than rebels.

John (smiling):

That feels very current.

Twain:

History is just politics wearing different trousers.

Now—let me be blunt.

You have three voices.

- The Scholar – careful, precise, formidable.

- The Witness – humane, reflective, grounded.

- The Satirist – dry, sly, devastating.

When you combine all three?

You’re dangerous.

You don’t always let the third one out.

Why?

John:

Maybe I’m afraid of being dismissed.

Twain:

Every good writer is dismissed.

Wear it like a medal.

If fools don’t misunderstand you, you’re not trying hard enough.

John:

What about style? Sentence-level writing?

Twain:

You’re clean. Clear. Honest.

But sometimes too polite.

Every once in a while, let a sentence misbehave.

Let it surprise you.

A good sentence should feel like it had a mind of its own and barely agreed to cooperate.

John (laughing):

That’s wonderful.

Twain:

Now—your future.

You’re not trying to become me.

Good.

The world already had me. It needs you.

You are writing for people who are tired of being lied to, simplified, manipulated, and shouted at.

You treat them like adults.

That’s rare.

That’s why they trust you.

If you want to grow:

Tell one more story per essay than feels necessary.

Cut one paragraph of explanation.

Add one moment of human vulnerability.

Let humor off the leash.

And never stop being irritated by nonsense.

Civilization runs on people who are politely annoyed.

John (after a pause):

Do you think I’m… really a writer?

Twain (leans forward):

Let me answer that carefully.

Writers write to be admired.

Authors write to be remembered.

You write to be useful.

That’s the hardest kind.

And the most honorable.

So yes.

You’re a writer.

Now stop worrying and go bother some readers.

They need you.

(A riverboat horn sounds. Twain stands, tips an imaginary hat.)

Twain:

Same porch next century?

John:

I’ll bring the coffee.

Twain:

I’ll bring the trouble.

Conclusions:

I hope you enjoyed my little fantasy here. I think there were some things I learned about myself and my writing from my dialogue with Mr. Twain. I know many of you who read my blogs are also writers. Writing is a very interesting craft. It is something that we can get better at all of our lives. We can always find a better way to say things. A more interesting phase or turn of the words. We can always make a more powerful statement. That to me is the beauty of the art.

Feb 12, 2026 @ 13:04:19

Loved this! Especially “you march your reader across those bridges like a drill sergeant.” Indeed. In my last book there is a chapter wherein I have a conversation with Dr. Freud. However, I didn’t have the use of an AI assist.

I’d be honored if you’d give it a read, sir.

LikeLike

Feb 12, 2026 @ 14:25:23

I would love to Mark. Can you send me a link to it. I will be out of town for the next week but will read it when I return.

LikeLiked by 1 person