Recently, I read that Trump is proposing the U.S. military begin the construction of a new class of battleships called “Trump Class” or as the press is labeling them “The Golden Fleet.” Each of these ships will have a realistic (not the bullshit projected cost by defense contractors) final cost of $30 billion apiece. If three are built—as is being discussed—we are looking at a price tag approaching $100 billion.

That number is so large that it becomes abstract. When figures reach this scale, they stop meaning anything at all. So with the help of my AI partner Metis, I tried an experiment: What if we forced that number back into human terms?

I asked Metis a very simple question:

What else could $100 billion buy if applied directly to the daily needs of American families?

To keep this grounded, I used conservative, real-world assumptions—not best-case fantasies.

The Assumptions

To avoid cherry-picking, I chose modest, mainstream benchmarks:

- A reliable used car: a 3-year-old Toyota Corolla or Honda Civic

Average cost: $20,000 - Food for a family of four using the USDA Thrifty Food Plan

Annual cost: $9,500 - A two-bedroom home, roughly 2,200 square feet

Average cost: $350,000

Then I asked the same question three times:

What does $100 billion buy—if we buy only this one thing?

Option One: Transportation

At $20,000 per vehicle, $100 billion would purchase:

5,000,000 reliable used cars

Five million.

That’s not a subsidy.

Not a tax credit.

Not a loan.

That is five million families with dependable transportation—the difference between:

- Holding a job or losing it

- Making a medical appointment or missing it

- Participating in society or being stranded at its margins

Transportation isn’t a luxury in America. It’s infrastructure for survival.

Option Two: Housing

At $350,000 per home, $100 billion would fund approximately:

286,000 homes

That’s enough housing for nearly one million people.

For perspective:

- It could dramatically reduce homelessness nationwide

- Stabilize entire regions

- Lower healthcare, policing, and emergency service costs downstream

Housing is not merely shelter. It is the foundation upon which everything else—health, education, employment—rests.

Option Three: Food Security

Using the USDA Thrifty Food Plan, $100 billion could provide one year of food for:

Over 10.5 million families of four

That’s 42 million people.

More than the population of California.

In a nation where food insecurity still affects tens of millions, this single line item could eliminate hunger—not as charity, but as policy.

Each ship carries not just steel and weapons—but foregone lives improved.

The Real Question:

This is not an argument against defense. This isn’t about ships versus cars or homes.

It is a challenge to unexamined assumptions.

What kind of security do we believe actually sustains a nation?

- Military security protects borders

- Economic security protects civilization itself

We speak of “national security” almost exclusively in military terms, yet:

- Hunger destabilizes families faster than any foreign power

- Homelessness erodes communities more reliably than missiles

- Economic security strengthens democracies from the inside out

- Food, shelter, and mobility:

- Reduce crime

- Improve health outcomes

- Stabilize families

- Increase productivity

- Lower long-term government costs

From a Deming-style systems view (which considers this as an investment vs. expense thinking taken to its logical conclusion. From a systems perspective, this is a classic case of short-term protection versus long-term stability.

Or to put it plainly:

A nation is not secure when its people are hungry, homeless, and one paycheck away from collapse—no matter how powerful its navy may be.

Conclusions:

When budgets reach into the tens of billions, morality becomes invisible unless we deliberately restore it.

Every dollar spent reflects a value choice.

Every budget is a moral document.

The question is not whether we can afford battleships.

The question is:

What kind of country do we believe we are protecting—and for whom?

I have met people who say, “I never eat Mexican food.” They say this as though it were some badge of honor. I want to ask what type of Mexican food do they not eat? Does their exclusion of Mexican food extend to deserts like fried ice cream or drinks like Tequila or is it simply tacos and burritos that they do not eat? I have met people who say, “I never eat fish.” I usually ask them why and I often hear the reply “they taste too fishy.” I want to ask them if they ever eat meat that tastes too meaty, but instead I usually ask them if their antipathy extends to crustaceans, mollusks, and cephalopods. I can see the disapproval in my spouse’s eyes when I pursue this line of questioning.

I have met people who say, “I never eat Mexican food.” They say this as though it were some badge of honor. I want to ask what type of Mexican food do they not eat? Does their exclusion of Mexican food extend to deserts like fried ice cream or drinks like Tequila or is it simply tacos and burritos that they do not eat? I have met people who say, “I never eat fish.” I usually ask them why and I often hear the reply “they taste too fishy.” I want to ask them if they ever eat meat that tastes too meaty, but instead I usually ask them if their antipathy extends to crustaceans, mollusks, and cephalopods. I can see the disapproval in my spouse’s eyes when I pursue this line of questioning.

After exploring the vast variety of Mexican foods, I discovered that the tasty and hearty Menudo soup is chock full of tripe. Many Latinos as well as Gringos in the Southwest will not eat Menudo. Several years ago, after I started dating Karen, I was introduced to Lutefisk. At first I found the texture somewhat off putting. Over time, by adding butter or cream sauce I discovered the joy of eating Lutefisk around the holidays. It is a Scandinavian tradition in homes much like Menudo is in Mexican homes. Paradoxically, many Scandinavians loath Lutefisk. The derivation of such foods leads many to disavow them. I confess to the same attitude towards an Italian dish known as Pasta a Fagioli which my mother loved to make. I left home swearing to never eat any again.

After exploring the vast variety of Mexican foods, I discovered that the tasty and hearty Menudo soup is chock full of tripe. Many Latinos as well as Gringos in the Southwest will not eat Menudo. Several years ago, after I started dating Karen, I was introduced to Lutefisk. At first I found the texture somewhat off putting. Over time, by adding butter or cream sauce I discovered the joy of eating Lutefisk around the holidays. It is a Scandinavian tradition in homes much like Menudo is in Mexican homes. Paradoxically, many Scandinavians loath Lutefisk. The derivation of such foods leads many to disavow them. I confess to the same attitude towards an Italian dish known as Pasta a Fagioli which my mother loved to make. I left home swearing to never eat any again. Some of these low-cost and nutritious peasant foods have become quite popular now as people look back to their early roots. An example of such a food dish is the Italian Pasta e Fagioli which I mentioned earlier. This is a dish comprised of beans and macaroni. Beans and macaroni form a “whole protein” which means you get all the amino acids you need without having to eat meat. A protein is considered “complete” when it has the nine essential amino acids in somewhat equal amounts. Almost every country in the world has some staple food items that provide whole protein. In poorer cultures, livestock was valued for its ability to help farm crops and produce milk. In places like India, livestock was made sacred as a way to prevent killing a valuable resource. Cows were more valuable alive than they were dead.

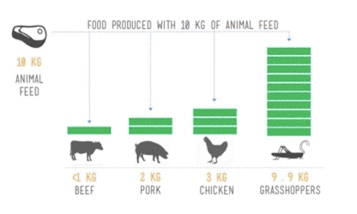

Some of these low-cost and nutritious peasant foods have become quite popular now as people look back to their early roots. An example of such a food dish is the Italian Pasta e Fagioli which I mentioned earlier. This is a dish comprised of beans and macaroni. Beans and macaroni form a “whole protein” which means you get all the amino acids you need without having to eat meat. A protein is considered “complete” when it has the nine essential amino acids in somewhat equal amounts. Almost every country in the world has some staple food items that provide whole protein. In poorer cultures, livestock was valued for its ability to help farm crops and produce milk. In places like India, livestock was made sacred as a way to prevent killing a valuable resource. Cows were more valuable alive than they were dead. A few years ago, at the annual Gustavus Adolphus Nobel Conference the subject was on food production. A number of experts claimed that the day will come when we will no longer be able to afford a practice so barbaric and wasteful as to slaughter animals for meat eating. There is an abundance of insects on this earth that could provide an almost endless low-cost supply of protein and minerals to our diets. Most people respond to thoughts about eating insects with something like “I could never eat bugs.” My retort is “well you don’t eat bloody chickens or bloody cows do you?” The insects would be processed, and they would provide a grain that could be used in various ways like we use wheat or corn meal. I get blank stares.

A few years ago, at the annual Gustavus Adolphus Nobel Conference the subject was on food production. A number of experts claimed that the day will come when we will no longer be able to afford a practice so barbaric and wasteful as to slaughter animals for meat eating. There is an abundance of insects on this earth that could provide an almost endless low-cost supply of protein and minerals to our diets. Most people respond to thoughts about eating insects with something like “I could never eat bugs.” My retort is “well you don’t eat bloody chickens or bloody cows do you?” The insects would be processed, and they would provide a grain that could be used in various ways like we use wheat or corn meal. I get blank stares.

Thus, the question arose in my mind about the difference or relationship between appreciation and gratitude. Perhaps this is like asking how many angels can dance on the head of a needle, but I thought the question deserved some reflection. Is the relationship between gratitude and appreciation similar to the relationship between tolerance and respect?

Thus, the question arose in my mind about the difference or relationship between appreciation and gratitude. Perhaps this is like asking how many angels can dance on the head of a needle, but I thought the question deserved some reflection. Is the relationship between gratitude and appreciation similar to the relationship between tolerance and respect? If you do not like to try new things, you should not travel. One of my mottos is “I have never met a food I did not like.” Karen and I eat at street vendors. We often shop locally and pick out foods that we do not even know what they are. When we were on Naxos, we found a meat market. We entered and were greeted with a variety of skinned animals hanging from hooks. There were no labels on these various creatures. We assumed they sold the meat in kilos, so we asked for a ½ kilo of this and ½ kilo of that. We decided that we would take the meats or whatever they were back to our little apartment and cook them. We figured that once we did this, we might be able to guess what we were eating. This was many years ago and I do not think we ever figured out what we were eating. The food was good and twenty-five years later we are alive and kicking. It was a great adventure. One that we have replicated many times.

If you do not like to try new things, you should not travel. One of my mottos is “I have never met a food I did not like.” Karen and I eat at street vendors. We often shop locally and pick out foods that we do not even know what they are. When we were on Naxos, we found a meat market. We entered and were greeted with a variety of skinned animals hanging from hooks. There were no labels on these various creatures. We assumed they sold the meat in kilos, so we asked for a ½ kilo of this and ½ kilo of that. We decided that we would take the meats or whatever they were back to our little apartment and cook them. We figured that once we did this, we might be able to guess what we were eating. This was many years ago and I do not think we ever figured out what we were eating. The food was good and twenty-five years later we are alive and kicking. It was a great adventure. One that we have replicated many times. I was forty years old before I had my first trip out of the USA. I had always wanted to travel and my four years in the military had not provided me the opportunity to travel. Later on, I became so busy with school and work that traveling seemed like a remote luxury. One day I was on a plane coming back from Thompson, Manitoba. (Canada does not count as foreign travel.) I had been working with a mining client that week and was now headed home. Next to me sat a young woman holding a travel guide to Spain. It was May and schools were getting out for the summer. I remarked “Are you going to Spain?” “Yes,” she replied. “Oh”, I said, “you must be very excited.” She answered somewhat petulantly, “No, I went there last summer but my parents wanted me to go again since I am studying Spanish.”

I was forty years old before I had my first trip out of the USA. I had always wanted to travel and my four years in the military had not provided me the opportunity to travel. Later on, I became so busy with school and work that traveling seemed like a remote luxury. One day I was on a plane coming back from Thompson, Manitoba. (Canada does not count as foreign travel.) I had been working with a mining client that week and was now headed home. Next to me sat a young woman holding a travel guide to Spain. It was May and schools were getting out for the summer. I remarked “Are you going to Spain?” “Yes,” she replied. “Oh”, I said, “you must be very excited.” She answered somewhat petulantly, “No, I went there last summer but my parents wanted me to go again since I am studying Spanish.” I did not say anymore to the young woman, but I thought “My, would I love to go to Spain or anyplace for that matter.” Then and there in that moment, I made up my mind. Karen and I were going to travel. We were going to see the world. When I arrived home, I shared my decision and determination with Karen. She was delighted but wondered how we would manage it. We have since been to 33 countries for a total of about 25 or more trips. We like to go to one country and see various sections of it rather than trying to see the whole of Europe or Asia in one trip. Usually we go for three weeks or so. We are very budget oriented and try to behave like pilgrims rather than like tourists. Our trips are usually a balancing act between being a pilgrim and being a tourist.

I did not say anymore to the young woman, but I thought “My, would I love to go to Spain or anyplace for that matter.” Then and there in that moment, I made up my mind. Karen and I were going to travel. We were going to see the world. When I arrived home, I shared my decision and determination with Karen. She was delighted but wondered how we would manage it. We have since been to 33 countries for a total of about 25 or more trips. We like to go to one country and see various sections of it rather than trying to see the whole of Europe or Asia in one trip. Usually we go for three weeks or so. We are very budget oriented and try to behave like pilgrims rather than like tourists. Our trips are usually a balancing act between being a pilgrim and being a tourist.