Introduction:

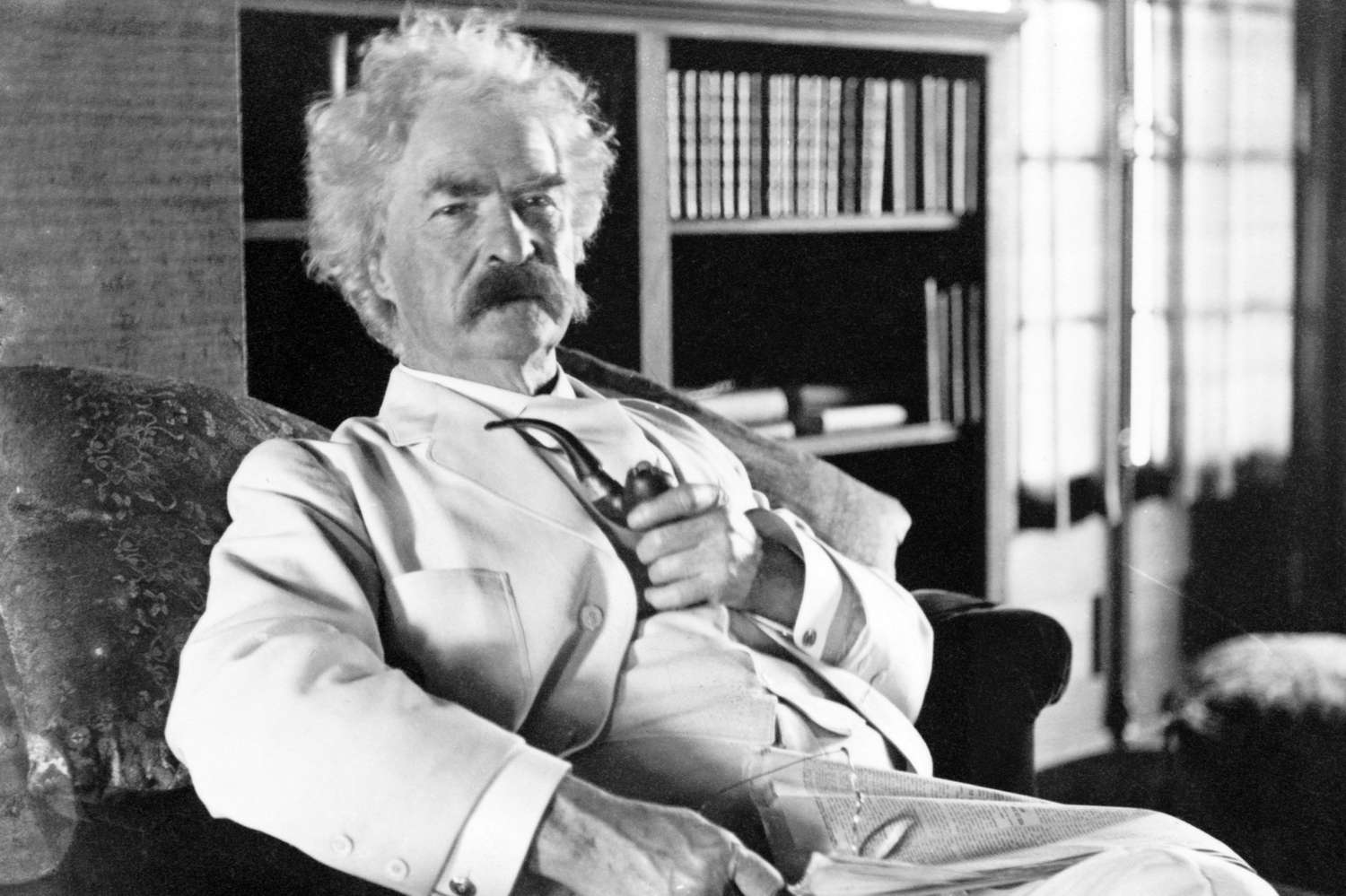

During the 80’s when I was in grad school at the University of Minnesota, I took several courses which discussed leadership. I had to write several papers on leadership. I noted at the time, that if you went into the card file of any library in the state, the most numerous entries would be for the subject of either Christianity or Leadership. Not sure if they had any deeper connection except to be subjects that most people were interested in. How can I get to heaven and how can I be a better if not great leader? So here I am almost fifty years later writing another article (now called a blog) on leadership. The difference is that this time, I am relying on my AI assistant Metis, to provide the dialogue. She is an unbelievable helper who can search reams of data to put the “write” words in the mouths of the right people.

I selected several people for a round table discussion on leadership. Each of these people is in some way an expert on leadership. Either because their thoughts have guided leaders for centuries or because they themselves are recognized as great leaders. I am calling this discussion:

A Conversation Across Time

Participants:

Confucius – Chinese philosopher of moral governance. Perhaps no one in history has had more influence on the proper behavior of both leaders and subjects. The words and thoughts of Confucious still guide the lives of millions of people across the world.

Plato – Greek philosopher of the ideal state. If Confucius is the most eminent philosopher in the Eastern world, Plato easily ranks as the most eminent philosopher in the Western world. A student of Socrates and a teacher of Aristotle, the ideas of Plato have shaped Western philosophy for centuries.

Abraham Lincoln – U.S. President during the Civil War. Considered by many to one of the two greatest presidents in American history. Lincoln led a divided nation through the bloodiest war in American history and sought to heal the nation when it was over rather than exact retribution or revenge.

Simón Bolívar – South American revolutionary and liberator. Bolivar was a Venezuelan military officer and statesman who led what are currently the countries of Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela to independence from the Spanish Empire. He is known colloquially as El Libertador, or the Liberator of America. He is regarded as a hero and national and cultural icon throughout Latin America. The nations of Bolivia and Venezuela (as the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela) are named after him, and he has been memorialized all over the world in the form of public art or street names and in popular culture.

Nelson Mandela – Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was a South African anti-apartheid activist and statesman who was the first president of South Africa from 1994 to 1999. He was repeatedly arrested for seditious activities and was unsuccessfully prosecuted in the 1956 Treason Trial. All total, Mandela spent more than twenty seven years in prison for fighting the apartheid state of South African. After leaving prison in 1990, Mr. Mandela became the country’s first Black head of state and the first elected in a fully representative democratic election. Globally regarded as an icon of moral leadership, peace, democracy and social justice, he received more than 250 honors, including the Nobel Peace Prize. He is held in deep respect within South Africa, where he is often referred to by his Thembu clan name, Madiba, and described as the “Father of the Nation”. Mandela is widely considered one of the greatest and most admired figures of the 20th century.

So, there you have it. A brief history of some of the panelists who have agreed to cross time and borders and sit down together for a discussion on “What makes a great leader?” This is no trivial subject. I hope that you will read what they have to say and take it to heart. Please feel free to share their thoughts with anyone you think might benefit from them. We live in a perilous time, not the least of which is due to a failed conception of “What makes a great leader?”

The Setting

In a quiet hall outside of time, five figures gather around a circular wooden table. Each has carried the weight of leadership, whether through philosophy or action. They have come to discuss a single question:

What makes a great leader?

Confucius Speaks

Confucius:

If we wish to speak of great leadership, we must begin with virtue. A ruler who governs by virtue is like the North Star—steady in its place while all the other stars revolve around it.

A leader must cultivate ren, benevolence toward others. Without benevolence, power becomes tyranny. Without moral example, laws alone cannot guide the people.

In my teachings I often said that if the ruler is upright, the people will follow without orders. But if the ruler himself is crooked, then even many commands will not bring harmony.

Thus, the foundation of leadership is self-cultivation. One must first govern oneself before attempting to govern others.

Plato Responds

Plato:

Confucius, your emphasis on virtue aligns closely with my own reflections. In my dialogue The Republic, I argued that societies decay when leadership falls into the hands of those who crave power rather than wisdom.

The ideal leader, I proposed, is the philosopher-king—a person who has pursued truth and understands justice. Such a leader does not govern for personal gain but for the good of the whole society.

Most political systems fail because they elevate ambition rather than wisdom. The loudest voices, the wealthiest men, or the most cunning politicians often rise to power.

But true leadership requires something rarer: knowledge of the good.

Without wisdom, authority becomes merely a contest for domination.

Lincoln Reflects

Lincoln:

Gentlemen, I must confess that I never considered myself either a sage or a philosopher-king. I was a country lawyer who found himself presiding over a nation tearing itself apart.

Yet I agree that moral purpose is central to leadership. During the American Civil War, the question before us was not merely political—it was moral. Could a nation founded on liberty survive while millions remained enslaved?

A leader must sometimes make decisions that will divide the country and bring great suffering. The responsibility weighs heavily.

What sustained me was a simple principle: government must remain accountable to the people, and its purpose must be to expand human freedom.

But I would add something else.

A great leader must possess humility.

The presidency taught me daily how limited one man’s understanding can be. Listening to critics—even harsh ones—can prevent terrible mistakes.

Bolívar Enters the Debate

Bolívar:

President Lincoln, your words resonate with my own experience in the wars for independence in South America.

I fought for decades to free nations from Spanish rule. In those struggles, leadership required not only ideals but also relentless determination.

Armies had to be organized. Alliances had to be built. Revolutions had to survive betrayal, fatigue, and defeat.

I dreamed of a united Latin America—a federation strong enough to resist foreign domination. But I learned that political freedom alone does not guarantee stability.

Nations newly freed from tyranny often struggle with factionalism and chaos.

Thus, leadership must balance liberty and order.

Too much authority risks dictatorship. Too little authority invites anarchy.

Finding that balance may be the hardest task any leader faces.

Mandela Speaks Quietly

Mandela:

General Bolívar, your words about balancing liberty and order remind me of the moment South Africa emerged from apartheid.

For many years I was imprisoned by a government that denied basic rights to the majority of its people. When freedom finally came, our nation faced a choice.

We could seek revenge—or we could seek reconciliation.

Leadership in that moment required restraint. Anger can mobilize people in a struggle, but it can also destroy a fragile peace once victory is achieved.

A leader must understand the emotions of the people yet not be ruled by them.

I learned something during my years in prison: the greatest leaders are those who can transform bitterness into hope.

Without forgiveness, nations remain prisoners of their past.

Plato Raises a Question

Plato:

Mandela, your example is admirable. Yet I wonder: can we rely on moral character alone to produce wise leadership?

History suggests that societies often choose leaders poorly.

Should we not design institutions that ensure the most capable and knowledgeable individuals rise to power?

Lincoln Answers

Lincoln:

Your concern is well taken. Democracies do not guarantee wise leaders. They merely allow the people to choose them.

But I would argue that democratic systems possess a corrective mechanism.

Bad leaders can eventually be removed.

Autocracies, even when led by brilliant rulers, risk catastrophic failure if the leader becomes corrupt or delusional.

The challenge is not simply choosing great leaders—it is building systems that survive imperfect ones.

Confucius Returns to Virtue

Confucius:

Systems are important, yet institutions alone cannot create harmony.

If those who occupy positions of authority lack virtue, even the finest laws will be twisted to serve selfish ends.

Therefore, the education of future leaders must emphasize moral character as much as knowledge.

In my time I believed that officials should be selected based on learning and ethical conduct.

Without moral cultivation, leadership becomes a contest for wealth and status.

Bolívar Reflects on Power

Bolívar:

I must add a warning drawn from bitter experience.

Revolutions often begin with noble ideals. Yet the exercise of power can corrupt even those who once fought for freedom.

I myself was accused of becoming too powerful in the nations I helped liberate.

A leader must constantly guard against the temptation to believe that only he can save the nation.

History is filled with such figures—and they rarely end well.

Mandela Adds Perspective

Mandela:

That temptation is real.

One of the most important decisions I made was to serve only a single term as president. Many urged me to remain in power longer.

But institutions must grow stronger than individuals.

A great leader should prepare the country for a future in which he or she is no longer necessary.

Plato Considers the Human Condition

Plato:

Listening to all of you, I begin to see a pattern.

Great leadership may not come from a single quality but from the balance of several virtues.

Wisdom, moral character, humility, courage, and restraint.

The tragedy is that these qualities rarely appear together in one person.

Lincoln Smiles

Lincoln:

That may be why history remembers so few truly great leaders.

The office itself does not confer greatness. Many hold power; few rise above it.

Leadership reveals character under pressure.

Confucius Concludes the Moral Lesson

Confucius:

If I may summarize: a leader must first become a good human being.

Virtue inspires trust.

Trust creates legitimacy.

Legitimacy produces harmony.

Without these elements, authority becomes fragile.

Mandela’s Final Reflection

Mandela:

And perhaps the most important truth is this:

Leadership is not about elevating oneself above others.

It is about lifting others so that they may stand on their own.

When ordinary people believe they can shape their own destiny, leadership has succeeded.

The Table Falls Silent

The five figures pause. Across centuries and continents, they have approached the same question from different paths.

Great leadership, it seems, is not merely the exercise of power.

It is the disciplined use of power in service of justice, unity, and human dignity.

As the discussion ended, it became clear that these leaders—though separated by centuries, cultures, and political systems—shared a surprising degree of agreement about the foundations of leadership. Each had experienced power in very different circumstances: revolution, civil war, philosophy, moral teaching, and national reconciliation.

Yet when their insights are distilled, a common set of principles begins to emerge. The following leadership lessons reflect the areas of strongest consensus among them—qualities that appear again and again whenever history produces a truly great leader.

Leadership Principles Emerging from the Dialogue

- Moral Character is the Foundation of Leadership

Confucius emphasized that leadership begins with personal virtue. Without integrity, authority becomes self-serving and corrupt. A leader’s behavior sets the tone for the entire society. When leaders demonstrate honesty, restraint, and compassion, these qualities tend to spread throughout the institutions they govern.

- Leadership Requires a Commitment to Justice

Plato and Lincoln both stressed that leadership must ultimately be guided by a commitment to justice. Power without moral direction easily becomes tyranny. Leaders must pursue what is right for society as a whole rather than what benefits themselves or a small elite.

- Wisdom Must Guide the Use of Power

Plato’s idea of the philosopher-king reminds us that leadership is not merely a popularity contest or a struggle for dominance. Effective leadership requires thoughtful judgment, careful reasoning, and an understanding of complex consequences. Decisions made without wisdom often create long-term damage even when intentions are good.

- Humility is Essential

Lincoln emphasized humility as one of the most important safeguards against catastrophic mistakes. Leaders who believe they possess all the answers often stop listening to others. Humility encourages consultation, debate, and learning—qualities that improve decision-making.

- Leaders Must Balance Liberty and Order

Simón Bolívar highlighted a problem faced by nearly every nation: how to preserve freedom while maintaining stability. Too much concentration of power can destroy liberty, but too little authority can produce chaos. Great leaders must continually balance these competing forces.

- The Ability to Unite People is Crucial

Nearly every participant touched on the importance of social unity. Lincoln sought to preserve the American Union, Bolívar tried to unify newly liberated nations, and Mandela worked to reconcile a deeply divided South Africa. Leadership often requires building bridges across differences in order to maintain a functioning society.

- Restraint and Self-Control are Marks of Great Leadership

Mandela emphasized the importance of restraint, especially after victory in political struggles. Leaders must sometimes resist the emotional pressures of revenge, anger, or triumphalism. The ability to step back and choose reconciliation over retaliation can determine whether a nation heals or descends into new conflict.

- Institutions Matter as Much as Individuals

While much of the dialogue focused on personal qualities, Lincoln and Mandela both emphasized the importance of institutions that outlast individual leaders. Democracies and stable governments depend on systems of accountability, laws, and norms that limit abuses of power.

- Great Leaders Prepare the Next Generation

Mandela’s decision to step down voluntarily illustrated an important principle: leadership should strengthen society so that it does not depend on one person. Great leaders cultivate future leaders and ensure that institutions remain strong after they leave office.

- Leadership is Ultimately Service

Perhaps the most powerful theme emerging from the discussion is that leadership is not about personal glory or domination. At its best, leadership is an act of service to others. Leaders succeed when they help citizens flourish, protect their freedoms, and create conditions in which people can build meaningful lives.

Hannah Arendt Arrives

Hannah Arendt is one of the most brilliant philosophers and thinkers of the twentieth century. Her book “The Banality of Evil” is one of the great analyses in history of what leads men and women to unspeakable acts of cruelty and immorality. Her works cover a broad range of topics, but she is best known for those dealing with the nature of wealth, power, fame, and evil, as well as politics, direct democracy, authority, tradition, and totalitarianism. She is also remembered for the controversy surrounding the trial of Adolf Eichmann, for her attempt to explain how ordinary people become actors in totalitarian systems, which was considered by some an apologia, and for the phrase “the banality of evil”. Her name appears on the names of many journals, schools, scholarly prizes, humanitarian prizes, think-tanks, streets, stamps and monuments; and is attached to other cultural and institutional markers that commemorate her thought.

Hannah Arendt:

I realize that you men are too smart to have forgotten a women’s perspective, so I will simply assume that somehow my invitation to this discussion was lost. However, arriving late does have its advantages. It allows me to listen carefully to what each of you distinguished gentlemen has said—and as often happens when one arrives last, it appears I will also have the final word.

Now I do not claim to be a great leader. My life has been spent mostly observing politics rather than practicing it. Yet in studying the rise and fall of governments, revolutions, and the darker episodes of the twentieth century, I have learned something about the nature of power and leadership.

Professor Confucius reminds us that virtue is essential. Plato insists that wisdom must guide authority. President Lincoln speaks of humility and democratic accountability. General Bolívar warns of the fragile balance between liberty and order. President Mandela demonstrates the extraordinary strength required for reconciliation.

All of you are correct, and yet I would add an important distinction that history repeatedly teaches us: power and leadership are not the same thing.

Power, in the political sense, does not arise from a single leader’s virtue or intelligence. True power emerges when people act together, when they recognize a shared purpose and agree to build something in common. Authority imposed from above may command obedience for a time, but it rarely endures.

The greatest leaders therefore do something quite subtle. They do not merely rule or persuade; they create conditions in which citizens themselves become participants in the public life of their society.

When leadership succeeds in this way, power no longer resides in the leader alone. It resides in the collective will of the people.

And that, I believe, is the only form of power that can sustain a free society.

In Summary

John:

The conversation suggests that great leadership is not defined by charisma, popularity, or raw power. Instead, it arises from a combination of moral character, wisdom, humility, and a genuine commitment to the well-being of others.

Across centuries and continents, these thinkers seem to agree on one central truth:

Leadership is not about ruling over people—it is about guiding a society toward justice, stability, and human dignity.

The End