When we speak of truth, beauty, and goodness, we often imagine three separate pursuits — the scholar seeking truth, the artist seeking beauty, and the saint seeking goodness. Yet Pope Francis and the great philosophers before him remind us that these three are not rivals but reflections of the same divine source. Each reveals a different aspect of reality, and only when all three are in harmony does the human spirit find peace.

Tradition tells us that truth belongs to the intellect, beauty to the heart, and goodness to the will. Truth teaches us to see, beauty teaches us to feel, and goodness teaches us to choose. In that triad we discover the anatomy of the soul — knowing, loving, and willing, each distinct yet inseparable.

But there is another path by which these virtues speak: the language of art and music. Long before we understood moral codes or philosophical systems, humanity painted, danced, and sang. In rhythm and color, in sound and silence, we expressed truths too deep for logic and too vast for words. Art and music, properly understood, are not escapes from reality — they are revelations of reality’s depth.

Beauty as the Gateway to the Soul

Beauty is the most immediate of the transcendentals. Truth demands patience, goodness requires effort, but beauty strikes us like lightning. It does not ask permission. A single note, a brushstroke, or a line of poetry can pierce our defenses and open the heart where argument cannot.

This is why great art has moral and intellectual power. It awakens us from indifference. The experience of beauty — genuine beauty, not the glamour of surface or sentiment — lifts the soul toward truth and goodness without coercion. It shows us what could be, and in doing so, reminds us what should be.

Aquinas called beauty “the splendor of truth.” The artist does not invent beauty but unveils it. Every authentic work of art — whether sacred or secular — is a momentary unveiling of reality’s inner harmony. It is truth made radiant, goodness made alluring. Beauty does not lecture; it invites. It does not command; it beckons.

The Role of the Artist

Artists are translators between the visible and invisible worlds. They take the raw materials of existence — light, sound, form, gesture — and reveal within them an order we might otherwise overlook. In doing so, they help us perceive truth through the lens of beauty.

A number of years ago, my first wife left me for another man. He was also married but decided not to leave his wife. My wife (Julie) and I reconciled and agreed to first resolve some issues by visiting a councilor. These efforts did not go very well. I was angry and hurt. I did not know what I had done wrong. My wife was also hurt and angry. I had always thought that we had a lot in common. At one of our first counseling sessions, the councilor noted that I did not display any emotions. I was quite proud of being rationale and not letting feelings get in the way of my world. In fact, I thought Spock was too emotional despite his public image as being stoic and logical.

The councilor mentioned my lack of emotions to my wife. Her reply stunned and hurt me very much. She said, “I always thought everyone had feelings, but I finally came to believe that John has no feelings.” I left that counseling session resolved to find some of the feelings that I had ignored. I decided the best way was to try to be more creative and less rationale. I signed up for art classes and ballet classes and decided to listen to more classical music. It was another nine months or so before Julie and I finally reconciled. During this period, I actually participated in a ballet, painted several nature pieces (which I thought were quite good) and spent days at the library listening to as much classical music as possible.

When art forgets truth, it becomes hollow display. When it forgets goodness, it becomes manipulation. But when truth and goodness dwell within beauty, art becomes what it was always meant to be: a mirror of creation’s wholeness. I was looking for my wholeness and my humanity which are also inseparable.

The artist’s vocation, then, is not self-expression alone but world-expression — to make the invisible visible, to translate the ineffable into form. The true artist is not a manufacturer of objects but a servant of insight. Their success is measured not by applause but by the awakening they cause in others. In my case, it was an awakening in myself. Art and music became the pillars of my salvation. I rediscovered my humanity in them.

The Music of Being

Among all the arts, music comes closest to expressing the order of the soul. It moves directly through time, breath, and rhythm — the same elements that animate life itself. Every heartbeat, every inhalation, every step is a kind of music. When we listen to or create music, we participate in a pattern that mirrors the pulse of existence. Martin Luther said “”Next to the Word of God, music deserves the highest praise.” Karen has this quote framed in our dining room.

Music unites truth, beauty, and goodness in motion:

- Its structure and harmony express truth — order and proportion.

- Its melody and color express beauty — emotion and wonder.

- Its rhythm and purpose express goodness — direction and intention.

That is why even those who cannot explain music are changed by it. It aligns the intellect’s search for order, the heart’s hunger for beauty, and the will’s longing for purpose. To make or hear music well is to experience harmony not only in sound but in being.

When I was in the third grade at PS 171 in Brooklyn, NY, the teacher put all of us into a choir or singing group. She acted as the conductor and started us out singing some song that she had taught us. I sang along with the rest of the kids until suddenly, my teacher yelled “Who is making that noise?” “You (she pointed at me), it’s you.” “Don’t sing” she screamed at me. “Just open and shut your mouth.” That was 70 years ago and to this day, I do not sing. Oh, people say I should get over it, but they are not living in my shoes. I listen to music more than most people in the world. I love all types of music. But I do not play music, and I do not sing.

Plato believed musical education shaped character because harmony trained the soul toward moral order. The disordered person, he said, was “out of tune.” Modern psychology would agree that we feel peace when the elements of our life are in rhythm — thought, emotion, and action resonating together like chords in balance. In this sense, every moral life is a composition, every soul a symphony in progress. My soul resonates with music, and the music resonates in every fiber of my body. If I could be born again as anything, I would be a tenor singing in the great opera houses of the world. I love the passion, drama and lyrics that fuse life into melodies that make time stand still for me. Somehow the strains of music have a purgative effect on the pains and disappointments that can sometimes fill my life.

The Sacred and the Profane

Not all art is beautiful in the pleasant sense. Some truths are too painful to adorn. Yet even tragedy, if it reveals reality faithfully, can serve beauty’s higher calling. A requiem, a lament, or a poem of grief can be beautiful because it tells the truth of human suffering while still pointing toward transcendence. It is like watching a sad movie. We connect to others through the suffering that art and music can convey. Of course, music often conveys joy and happiness, but these are bonuses in a world today where suffering seems to be the norm.

Sacred art makes this explicit. It does not flatter the senses but reorders them toward the divine. The frescoes of Michelangelo, the cantatas of Bach, the icons of the Orthodox tradition — each embodies beauty that leads beyond itself. Their purpose is not entertainment but transformation. They invite us to see through the surface of the world into its divine origin.

But even the so-called profane arts can serve the same purpose when they reveal authentic experience. A rap song, a nursery rhyme, a portrait of a tree, a romantic novel — each can bear truth if it arises from sincerity and respect for life’s depth. I had an MRI today and as I listened to the banging, clanging, whistling and other sounds, I could hear a melody emerging. I thought of penning a song called “Melodies in an MRI.” The sacred is not confined to churches; it inhabits every honest act of creation.

The Moral Dimension of Beauty

Beauty’s moral power lies in its capacity to attract us toward goodness. Moral laws can instruct, but only beauty can enchant. We are moved to do good not merely by obligation but by love for what is good. Beauty provides that love.

This is why ugliness — deliberate distortion and cynicism — corrodes the soul. It teaches us that nothing matters, that form and harmony are illusions. When culture celebrates ugliness, it signals despair; when it honors beauty, it declares hope. True beauty does not deny suffering; it gives suffering meaning.

The 20th-century theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar wrote: “We no longer dare to believe in beauty, and we make of it a mere appearance in order the more easily to dispose of it.” He warned that without beauty, truth and goodness lose their persuasive power. In other words, without art and music, morality becomes sterile, and truth becomes abstract.

Beauty is not the soft edge of morality — it is its living energy. It whispers to the will, “Choose life, not despair.”

The Soul as an Instrument

If truth belongs to the intellect, beauty to the heart, and goodness to the will, then the soul is the instrument through which they resonate together. Like a violin, it must be tuned. The strings of mind, emotion, and desire can each sound discordant when isolated. Harmony arises only when they are stretched to the right tension and played in unity.

Art and music help tune the soul. When we create or contemplate beauty, we sense the right relation of parts to whole, of the finite to the infinite. We remember that life itself is composed — not chaos but cosmos. In that moment, we are most alive, most human, and perhaps most divine. The god we seek flames within us at these moments.

That tuning is not limited to artists. Every person can live artfully. A kind word spoken at the right time, a well-prepared meal, a garden tended with care — each is a small act of aesthetic and moral order. In that sense, the moral life and the artistic life are one: both seek to make the world more beautiful and more true. I find my muse in writing. I like to think that I am somewhat good at using words. When I was in high school, other students used to pay me to write their essays for them. I remember one friend who asked me to write something for him. I told him that he should do it himself. He said, “But you are so good at writing.” He was a musician, and I challenged him, “Is it possible to be a better musician if you do not practice?” He agreed practice was essential but said that he would rather practice playing music than practice writing. I wrote the essay for him. It was only logical as Spock would say.

The Silence Beyond the Sound

At the heart of music is silence. Without it, the notes have no shape. Silence frames beauty the way space frames form. Likewise, the soul needs silence to perceive truth and goodness. In our noisy age, we risk losing the capacity for this interior listening. Yet every deep encounter with art or nature — every moment when beauty stops us — restores that silence within. I learned to appreciate the beauty of music in my many hours sitting inside that library booth listening to the strains of Mozart, Beethoven, Bach and many other great musicians. I am fond of saying that I never “met a food that I did not like.” The same applies to music genres. There is something in every genre of music that speaks to my heart and my soul hears.

The silence after a great symphony or before a sunrise is not emptiness. It is presence — the awareness that life itself is music being played through us. To live in that awareness is to live in gratitude. Gratitude, in turn, is the purest harmony of truth, beauty, and goodness. Ingratitude, St. Ignatius said was the “Gateway to all sins.” How difficult it is to remember this for so many of us including myself.

Conclusion: Living Artfully

Art and music are not ornaments to life; they are its inner logic. They teach us that creation is not random but composed, that our task is not to control the score but to play our part faithfully. When truth informs our minds, beauty moves our hearts, and goodness directs our wills, we become participants in the divine symphony rather than spectators.

To live artfully is to live beautifully. To live beautifully is to live truthfully. And to live truthfully is to live for goodness.

In the end, every human life is a work of art in progress — sometimes dissonant, sometimes serene, always unfinished. Yet even our imperfections can contribute to the greater harmony if we keep tuning ourselves to the eternal themes of truth, beauty, and goodness. Perhaps this is the greatest truth that we all need to discover. As Pope Francis said “Truth, beauty and Goodness” are inseparable.

When we do accept this truth, we will find that the music of the soul is already playing, quietly, beneath the noise of the world — waiting only for us to listen.

Author’s Note:

Portions of this essay were developed in collaboration with “Metis,” my AI writing partner powered by OpenAI’s GPT-5. The ideas, direction, and final reflections are my own, shaped through a dialogue intended to illuminate and refine the themes explored here.

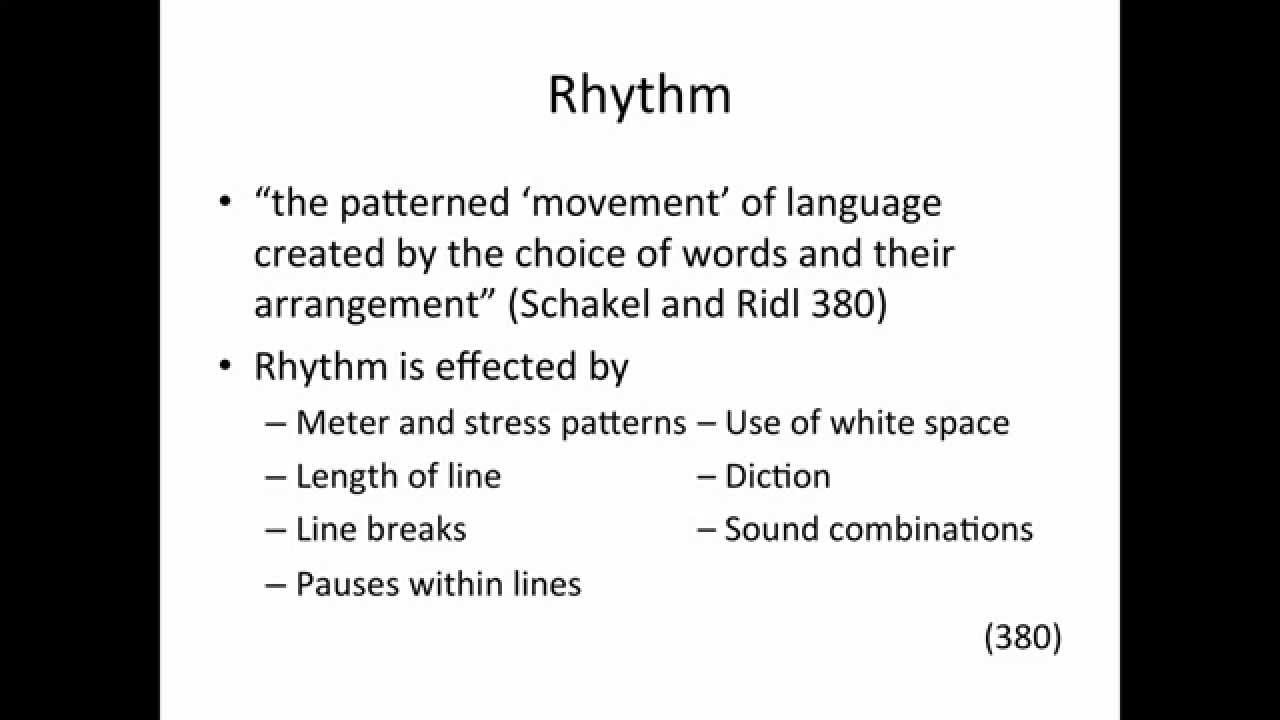

On some primal level, we all live by an unseen law of rhythm. The rhythm of the universe controls an eternal dance between the atoms and molecules that make up our existence. This natural rhythm imparts an inexorable symmetry to all of life. A regulated succession of strong and weak elements of opposite and contrasting conditions that becomes the master of all that we do. Buddhists call it the Yin and Yang of being.

On some primal level, we all live by an unseen law of rhythm. The rhythm of the universe controls an eternal dance between the atoms and molecules that make up our existence. This natural rhythm imparts an inexorable symmetry to all of life. A regulated succession of strong and weak elements of opposite and contrasting conditions that becomes the master of all that we do. Buddhists call it the Yin and Yang of being. In countless ways, we observe that there is fundamentally no difference between writing or between a piece of choreography and the changing climate. Creativity is carved out of the passion that is in everything we do. The body and mind embrace in a never-ending minuet. The music ebbs and flows. Our love is gentle, restrained, then wild and feral. Mornings, afternoons, evenings, and nights fuse with the seasons of spring, summer, fall and winter. The harsh gales of November resonate in the refrains of Tchaikovsky and Beethoven. “Summer Breeze” by Seals and Crofts ushers in the scorching days of July. Poetry rings out in the rap music of the streets while the mellow voices of choir singers comfort the soul. All things are one say the mystics. If my writing is one with all things, will the tempo of my words cool, heat, soothe or disrupt the fashions of life?

In countless ways, we observe that there is fundamentally no difference between writing or between a piece of choreography and the changing climate. Creativity is carved out of the passion that is in everything we do. The body and mind embrace in a never-ending minuet. The music ebbs and flows. Our love is gentle, restrained, then wild and feral. Mornings, afternoons, evenings, and nights fuse with the seasons of spring, summer, fall and winter. The harsh gales of November resonate in the refrains of Tchaikovsky and Beethoven. “Summer Breeze” by Seals and Crofts ushers in the scorching days of July. Poetry rings out in the rap music of the streets while the mellow voices of choir singers comfort the soul. All things are one say the mystics. If my writing is one with all things, will the tempo of my words cool, heat, soothe or disrupt the fashions of life?

We are all dust in the wind but our rhythms echo through the halls of time. The most unforgettable and amazing repetitions will continue as long as humans walk the earth. Coded in the numerous ways we have of capturing the rhythm of our lives. Some code in music, some in text and some in clay. Some codes are dynamic, some peaceful, some violent and some sad. We write our lyrics, pen our verses, create our stanzas, and design our choreography. All efforts guided by the unseen law of rhythm. Now we are hard, now we are brittle. Now we roar and now we snore.

We are all dust in the wind but our rhythms echo through the halls of time. The most unforgettable and amazing repetitions will continue as long as humans walk the earth. Coded in the numerous ways we have of capturing the rhythm of our lives. Some code in music, some in text and some in clay. Some codes are dynamic, some peaceful, some violent and some sad. We write our lyrics, pen our verses, create our stanzas, and design our choreography. All efforts guided by the unseen law of rhythm. Now we are hard, now we are brittle. Now we roar and now we snore.

The rhythm of life runs through our heart beats. It runs through literature. It runs through music. Great music has rhythms that exhibit great variation. Fast, slow, moderate than fast again. Interesting speakers have a sense of rhythm in their talks. Have you ever heard a lecture or a sermon without rhythm? It will put you to sleep in less than five minutes. Writing and speaking, just like music, must contain elements of rhythm. A heart without rhythm ceases to beat. Writing without rhythm is boring. Life without rhythm is death.

The rhythm of life runs through our heart beats. It runs through literature. It runs through music. Great music has rhythms that exhibit great variation. Fast, slow, moderate than fast again. Interesting speakers have a sense of rhythm in their talks. Have you ever heard a lecture or a sermon without rhythm? It will put you to sleep in less than five minutes. Writing and speaking, just like music, must contain elements of rhythm. A heart without rhythm ceases to beat. Writing without rhythm is boring. Life without rhythm is death.

When I grew up, the only art in our house was an Elvis on velvet painting that my mother had hanging over the living room sofa. We also had a wooden ship with metal sails and a clock that did not work built into the side of the ship. It was featured prominently on the mantle over our fake fireplace. Our furniture would have done the Salvation Army proud. I do not remember any other art besides Elvis displayed on our walls, floors, or ceilings. Neither my father or mother had any interest in art. My mother liked Elvis and that is why she got the painting.

When I grew up, the only art in our house was an Elvis on velvet painting that my mother had hanging over the living room sofa. We also had a wooden ship with metal sails and a clock that did not work built into the side of the ship. It was featured prominently on the mantle over our fake fireplace. Our furniture would have done the Salvation Army proud. I do not remember any other art besides Elvis displayed on our walls, floors, or ceilings. Neither my father or mother had any interest in art. My mother liked Elvis and that is why she got the painting.  When I think back upon my schooling, I do not recall ever having had a single class in art appreciation. We would occasionally go on field trips but usually to a library or a science museum. No one in my schools acknowledged the world of art. For blue collar kids like myself, the world of art had little relevance or practical use. Everyone knew that artists died poor. The great Van Gogh sold only one picture in his lifetime and that to a relative. The purchase of art was for the rich, spoiled, eccentric scions of old aristocratic families with more money than they knew what to do with.

When I think back upon my schooling, I do not recall ever having had a single class in art appreciation. We would occasionally go on field trips but usually to a library or a science museum. No one in my schools acknowledged the world of art. For blue collar kids like myself, the world of art had little relevance or practical use. Everyone knew that artists died poor. The great Van Gogh sold only one picture in his lifetime and that to a relative. The purchase of art was for the rich, spoiled, eccentric scions of old aristocratic families with more money than they knew what to do with.  When Karen and I first moved down to Arizona, we took a day to go and visit Scottsdale. Scottsdale is a wealthy upper-class community. Scottsdale is generally considered the most affluent large city in Arizona. The average income of a Scottsdale resident is $51,564 a year. The US average is $28,555 a year. According to Zillow.com, the typical price of a home in Scottsdale is $582,292. We walked around the downtown portion of Scottsdale and expected to see the usual mix of clothing stores, jewelry shops, antique shops, and restaurants. We were not surprised except when it came to the antique shops.

When Karen and I first moved down to Arizona, we took a day to go and visit Scottsdale. Scottsdale is a wealthy upper-class community. Scottsdale is generally considered the most affluent large city in Arizona. The average income of a Scottsdale resident is $51,564 a year. The US average is $28,555 a year. According to Zillow.com, the typical price of a home in Scottsdale is $582,292. We walked around the downtown portion of Scottsdale and expected to see the usual mix of clothing stores, jewelry shops, antique shops, and restaurants. We were not surprised except when it came to the antique shops.

Art reflects the beauty that life holds. Paintings portray ideals and impressions that intrigue and magnify the senses. Sculptures mirror the objects in our world that mystify us or that remind us of magnificent events. Pictures bring us to other places and times that would be forgotten without the images the photographer captures. Art does not attempt to simply mirror reality; it attempts to augment and enhance reality. Art can be a caricature which like a Rorschach text enables us to see many different visions. Art is a realization of values, norms, pain, happiness, the past, the present and the future. Art can simultaneously create fantasy and reality.

Art reflects the beauty that life holds. Paintings portray ideals and impressions that intrigue and magnify the senses. Sculptures mirror the objects in our world that mystify us or that remind us of magnificent events. Pictures bring us to other places and times that would be forgotten without the images the photographer captures. Art does not attempt to simply mirror reality; it attempts to augment and enhance reality. Art can be a caricature which like a Rorschach text enables us to see many different visions. Art is a realization of values, norms, pain, happiness, the past, the present and the future. Art can simultaneously create fantasy and reality. You may be rightly thinking, “But what good does art do me if I cannot afford to even walk into an art shop?” I often asked myself this same question. Why look at stuff that I could not afford? It took me years before I even ventured into an art museum. I have since visited the Louvre while in Paris and many other museums in the USA and in Europe. My attitude is now one of gratefulness that someone has purchased these magnificent works of art to share with the public. The vast majority of us could never begin to afford the pricelessness of these museum pieces. I strongly encourage you to visit an art museum sometime.

You may be rightly thinking, “But what good does art do me if I cannot afford to even walk into an art shop?” I often asked myself this same question. Why look at stuff that I could not afford? It took me years before I even ventured into an art museum. I have since visited the Louvre while in Paris and many other museums in the USA and in Europe. My attitude is now one of gratefulness that someone has purchased these magnificent works of art to share with the public. The vast majority of us could never begin to afford the pricelessness of these museum pieces. I strongly encourage you to visit an art museum sometime.  When it comes to art that I would like to own, it is simply a matter of what I can afford. The art world is full of overpriced works of art. Many would rebel at my labeling art this way. My critics would say that it was high priced and not “over” priced. That may well be. I have talked to a number of artists and the vast majority do not get paid for the value of their efforts and creativity. However, just like in athletics, a few stand out and are disproportionally rewarded for their efforts.

When it comes to art that I would like to own, it is simply a matter of what I can afford. The art world is full of overpriced works of art. Many would rebel at my labeling art this way. My critics would say that it was high priced and not “over” priced. That may well be. I have talked to a number of artists and the vast majority do not get paid for the value of their efforts and creativity. However, just like in athletics, a few stand out and are disproportionally rewarded for their efforts.

Once, as a new employee, I was attending my first department meeting with my co-workers and supervisor. I deemed it prudent to keep my mouth shut and observe. At the end of the meeting, my supervisor turned to me and noted, “Well, John, you haven’t said a word. What do you think? Give me your honest opinion.” I took her at her word and gave her my honest uncensored opinion. Big mistake, as I am sure you knew. Turns out my boss only liked “Honest Opinions” when they agreed with her opinions. A good mentor would have warned me of this peril before I put my foot in my mouth.

Once, as a new employee, I was attending my first department meeting with my co-workers and supervisor. I deemed it prudent to keep my mouth shut and observe. At the end of the meeting, my supervisor turned to me and noted, “Well, John, you haven’t said a word. What do you think? Give me your honest opinion.” I took her at her word and gave her my honest uncensored opinion. Big mistake, as I am sure you knew. Turns out my boss only liked “Honest Opinions” when they agreed with her opinions. A good mentor would have warned me of this peril before I put my foot in my mouth. me by giving me support and stimulation to be creative. I was thinking back over the years that I have been writing. My first paid article was in 1983. It was published in a San Francisco Men’s Journal. My piece was called “The Three Types of Male Intimacy.” I was paid about 25 dollars. It was not much but it felt like a start. I have since published about 40 journal articles, three books and over 600 blogs. It is a good thing that I never quit my day job since I could barely pay my monthly entertainment bill with the proceeds from my writing.

me by giving me support and stimulation to be creative. I was thinking back over the years that I have been writing. My first paid article was in 1983. It was published in a San Francisco Men’s Journal. My piece was called “The Three Types of Male Intimacy.” I was paid about 25 dollars. It was not much but it felt like a start. I have since published about 40 journal articles, three books and over 600 blogs. It is a good thing that I never quit my day job since I could barely pay my monthly entertainment bill with the proceeds from my writing.

“I do not know what writing awaits me,

“I do not know what writing awaits me,