Part I: Why Our Old Economic System No Longer Fits Our New Reality — Dr. J and Metis

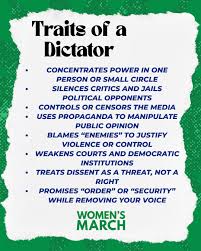

Before I begin the actual substance of this blog, I want to denounce the criminal activities now going on in Minnesota and being conducted by a Federal Agency. Under the guise of conducting Immigration enforcement, they are actually enforcing the vengeance and retribution of a madman in the office of POTUS. A man who takes revenge on people who he believes stand against him or who dare to speak out against him.

It is difficult to write the following blog knowing that many good people are rightfully preoccupied with the violence being conducted against the people of Minnesota. Nevertheless, this violence does not happen randomly or in a vacuum. This violence is not just the workings of a man who would be king. It is the result of a dangerously obsolete economic system which now threatens not only Americans but the entire world with more death and destruction as it tries to maintain its greed and avarice. In this effort, it is supported by greedy men and women who believe that the rest of the world exists solely to make them rich. It is system that supports inequality, racism, sexism, homophobia, xenophobia, anti-environmentalism and war. This will only get worse unless we address the underlying pathologies that stem from a system of Corporate Capitalism bent on owning the world.

- Introduction:

For most of my working life, I made a living helping organizations understand why systems fail.

- Not because people are lazy.

- Not because workers don’t care.

- Not because leaders are stupid.

But because structures quietly drift out of alignment with reality. I always liked to refer to the Law of Entropy to explain this phenomenon better.

Long before collapse becomes visible, warning signs appear—in data, in morale, in quality, in trust.

- I saw this in manufacturing firms.

- I saw it in service organizations.

- I saw it in public institutions.

And increasingly, I see it in our economy.

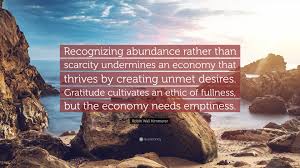

In an earlier essay, where I introduced what I called “Equalitarianism,” I argued that we are entering an era in which abundance will no longer be limited primarily by human labor, but by how we choose to organize ownership, access, and distribution.

This essay extends that argument. Because artificial intelligence and emerging energy technologies are now forcing that question out of theory and into daily life.

From the beginning of history, most economic systems rested on a simple and powerful assumption: human labor is the primary engine of value. People worked. Their work produced goods and services. Their wages allowed them to participate in the market. Demand fueled production. Production fueled employment. And the cycle continued. In economics, I taught that Land, Labor and Capital were the three cornerstones of any economic system.

This basic structure—imperfect but functional—underpinned industrial capitalism, the postwar middle class, and much of what we still call “the American Dream.”

But that structure is now under quiet, accelerating strain.

Artificial intelligence, advanced automation, and emerging energy technologies such as Nuclear Fusion and Quantum Computers are not merely “new tools.” They represent a major shift in how value is created. For the first time in history, we are approaching a world in which large portions of economic output can be generated with minimal human labor.

This is not a speculative future. It is already happening.

Algorithms write code, analyze medical images, manage logistics networks, design products, translate languages, generate text, and optimize financial systems. Machines increasingly learn from experience rather than instruction. Energy systems are becoming cleaner, more efficient, and potentially far more abundant. Data centers now rival heavy industry in economic importance.

These developments are often celebrated as breakthroughs. And in many ways, they are.

But they also expose a structural problem in our existing economic model.

Our system still assumes that most people will earn their living primarily by selling their labor. It assumes that productivity gains will translate into broad-based wage growth. It assumes that stable employment will remain the main mechanism by which individuals secure food, housing, healthcare, and dignity.

Those assumptions are becoming less reliable.

- The Quiet Unraveling of the Labor–Income Link

For decades, economists have observed a growing gap between productivity and wages. Output per worker has risen steadily. Median incomes have not kept pace. More people work multiple jobs. Benefits have eroded. Job security has weakened. Gig work has expanded. Pensions have disappeared. Healthcare costs have risen faster than wages.

These trends did not begin with AI. They reflect long-term structural shifts: globalization, financialization, deregulation, weakened labor institutions, and technological change. I have watched these changes up close. As an employment counselor in Wisconsin and Minnesota, I worked with people who had done everything “right”—steady work histories, technical skills, loyalty to their employers—only to find themselves displaced by restructuring and automation.

Many never fully recovered economically, despite their willingness to retrain and adapt. The system had moved on faster than they could.

AI accelerates these changes.

When software can perform cognitive tasks that once required years of training, the economic value of many forms of expertise declines. When automated systems replace routine work, the number of stable middle-income jobs shrinks. When firms scale with fewer employees, profits concentrate.

None of this requires malice. It emerges naturally from existing incentives.

From a narrow business perspective, replacing human labor with reliable machines is rational. From a systems perspective, it destabilizes the income foundation of the society.

An economy cannot function if too many people lack secure access to basic necessities.

Markets require participants with purchasing power. Democracies require citizens with a stake in the system. Communities require members who are not perpetually anxious about survival.

When the labor–income link weakens, all three are threatened.

- Technology Does Not Save Systems. Institutions Do.

There is a persistent belief that technology will “solve” our social problems. More growth, more efficiency, more innovation—these are assumed to generate prosperity automatically.

History suggests otherwise.

The Industrial Revolution produced extraordinary wealth. It also produced slums, child labor, dangerous factories, and extreme inequality. It took decades of political struggle, regulation, and institutional reform to translate industrial productivity into broad social benefit.

Electricity, mass production, and modern medicine did not create the middle class by themselves. Social Security, public education, labor protections, infrastructure investment, and progressive taxation did.

Technology created possibilities. Institutions determined outcomes.

The same is true today.

AI, automation, and potentially fusion energy could usher in an era of unprecedented material abundance. They could also entrench a new form of technological feudalism, in which a small group controls productive systems while the majority remain economically precarious.

The difference will not be determined by algorithms.

It will be determined by governance.

During my consulting years with the Process Management Institute, I saw how often organizations invested in new technologies without redesigning their underlying processes. The result was predictable: more complexity, higher costs, and disappointed expectations.

National economies are not immune to the same mistake.

- The Myth of “Natural” Markets

In an earlier two-part blog I wrote on the need for what I call an Equalitarian Economy. I argued that economic systems are never neutral. They encode values, incentives, and power relationships. What we often call “free markets” are in fact carefully constructed environments whose rules determine who benefits from growth, who bears risk and who will profit the most.

The technological changes now underway make the reality of this fact impossible to ignore.

Much of the resistance to new economic thinking rests on a myth: that markets are “natural” and self-regulating, while social policies and government policies are artificial intrusions.

In reality, every market is highly structured. Just like any competitive event (think football or soccer), it could not exist without rules, regulations and policies. The only systems that exist without rules are wars and even modern wars follow some rules and guidelines, albeit they are often ignored.

Property rights, contract law, corporate charters, intellectual property regimes, financial regulations, bankruptcy rules, labor standards, and tax systems are all human constructions. They shape who benefits from productivity and how risks are distributed.

Our current system reflects choices made over decades—often in response to past crises.

Social Security was created after mass elder poverty. Labor protections followed industrial exploitation. Banking regulations followed financial collapse. Medicare followed medical insecurity.

Each reform was called unrealistic when proposed. Each became indispensable.

Equalitarianism, as I have framed it elsewhere, belongs to this tradition. It is not an attempt to abolish markets or suppress innovation. It is an attempt to update the institutional architecture of capitalism for a world in which human labor is no longer the primary bottleneck.

- Why Income Alone Is Not Enough

Much contemporary discussion focuses on income support: basic income, tax credits, wage subsidies. These are important tools. But they are not sufficient by themselves. This is why, in my earlier work on Equalitarianism, I emphasized access over mere compensation. A society that treats survival as a market outcome rather than a civic guarantee eventually undermines its own legitimacy.

What people ultimately need is not money in the abstract. They need secure access to essentials: food, shelter, healthcare, energy, and connectivity.

When these become unaffordable, income becomes fragile. When they are protected, income becomes empowering.

An economy that guarantees access to essentials creates stability. One that leaves them fully exposed to market volatility creates chronic insecurity. In my former job as Employment Counselor for both the State of Minnesota (DES) and the State of Wisconsin (DILHR), I was acutely aware of the platitudes that government often gives in times of economic disruptions. I watched as NAFTA displaced over 9 million workers and our government stood by idly and told them they would need to get reeducated or retrained. Many men and women who never finished high school were told to go to college. Some who had severe disabilities from years of hard labor. Others who were making incomes that no one would pay anymore.

It broke my heart to think that I was part of the system that was throwing them to the proverbial wolfs. It did not surprise me when years later many of these same men and women came out to support Trump. His disdain for government was shared by many of these people. I repeat that many of these men and women never found regular jobs back in the mainstream economy.

Equalitarianism begins with this recognition: survival should not be contingent on perfect market performance. We have a zeitgeist wherein over one third of voters are willing to throw democracy out the window. Much of this willingness started when nine million people lost their livelihoods due to a seemingly uncaring government. Can you imagine the disruptions that AI will create in America when according to some estimates it will eliminate ½ of the jobs in the country? Perhaps more than 50,000,000 jobs will be displaced by AI.

- The Real Choice Ahead

The Equalitarian framework I previously outlined was not intended as a finished blueprint. It was an attempt to sketch the minimum institutional adjustments required for an economy to remain coherent in the face of accelerating automation.

The developments in AI and energy systems now make that sketch urgent. We are on the cusp of a new dynamic that will see the merger of AI and Fusion Energy. The dream for many years of an unlimited energy supply is now within our grasp. We must realign our economy to reflect that Data is now a more important driver of economic growth than physical or in many cases even intellectual power. If we do not create a system where all people have access to food, housing, data and education, we will default to a system that is so barbaric it will make any system of slavery that ever existed look benign.

As AI and advanced energy systems mature, societies will face a choice that will only make thing worse. We can allow productivity gains to concentrate, treating mass insecurity as collateral damage or we can respond with coercive systems: surveillance, policing, and repression to manage unrest. The alternative to these negative choices will reside in our empathy and compassion for others. We can redesign economic institutions to distribute abundance broadly and maintain social cohesion. We can redesign our present system based on love and justice for all.

- This is not a moral fantasy. It is a systems question.

Every complex system requires feedback loops that maintain stability. When income, access, and opportunity diverge too far, instability follows.

In Part II of this blog, I will explore what a functional alternative might look like—and how emerging technologies could support, rather than undermine, a more resilient economic order.

I want to thank my AI assistant Metis for input, research and help with this article. AI has become a valuable ally to me in my ongoing effort to imitate Paul Revere and his ride. Instead of a horse, my trusty steed is the Internet. My bullets are bytes and bits of information that I hope will arouse the populace to arms. We need a revolution to create a just and fair society for all based on the Democratic principles that once guided our Founding Father and Mothers.