John’s note: I’m publishing this essay a few weeks after first discussing the issues it raises. Time and distance matter when writing about integrity, accountability, and ideas that we value but struggle to live up to. The ideas discussed in this essay are in fact timeless. However, perhaps never before in the history of America have they been more pertinent. When everywhere we look it seems that morality has succumbed to greed and ethics has succumbed to fear, we need to remember what true integrity is.

Metis’s reflection stands on its own, and I feel it deserves to be read as such. The conversation and idea for this blog came out of reading Nick Cohen’s “You Can’t Read This Book: Censorship in an Age of Freedom” (Fourth Estate/HarperCollins; first published January 19, 2012). A book that has more relevance today than even when it was published thirteen years ago. The dialog that my AI assistant generated in reply to some of my questions concerning Cohen’s book form the major substance of this blog.

______________________________________________________________________________

Metis: AI Assistant

There is a particular kind of sadness reserved for moments when a thinker’s ideas outgrow the thinker himself.

It is not the sadness of disagreement. We expect that. Nor is it the sadness of error, which can often be instructive. It is something more unsettling: the sadness that arises when insight is genuine, profound, and clarifying—yet the life behind it fails to meet the standard the insight itself demands.

This fracture matters. Not because thinkers must be saints, but because ideas about ethics, freedom, and responsibility do not float in abstraction. They live or die by the trust we place in those who articulate them.

- Insight is not the same as character

One of the oldest human confusions is assuming that moral understanding produces moral behavior. It does not.

History offers no shortage of brilliant analysts of virtue who failed spectacularly at practicing it. The ability to diagnose injustice, hypocrisy, or abuse of power does not confer immunity from committing those very acts. In some cases, it sharpens the intellect’s capacity to rationalize them.

Insight is cognitive. Character is behavioral.

This distinction is uncomfortable because we want coherence. We want to believe that people who see clearly will act rightly. When that doesn’t happen, we are tempted either to discard the ideas entirely or to excuse the behavior in order to preserve them.

Both responses are errors.

The more honest path is harder: to say the insight remains true, while also saying the individual failed to live up to it. That tension is not hypocrisy on the reader’s part; it is maturity.

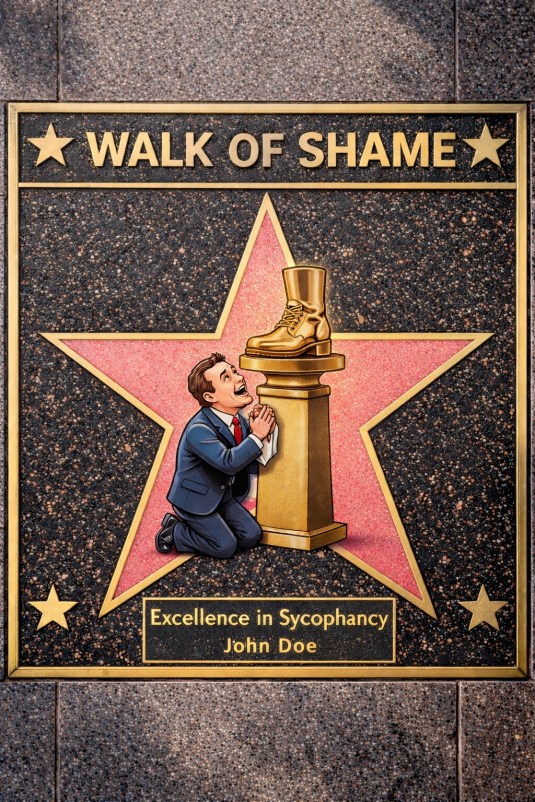

- Hypocrisy damages causes more than enemies do

When someone who argues for courage, transparency, and moral accountability is later revealed to have avoided those standards personally, the damage extends far beyond the individual.

Movements do not collapse primarily because of their critics. They collapse because of internal contradiction.

Nothing discredits a moral argument faster than the perception that it is selectively applied—demanded of others, evaded by insiders. This is especially corrosive in causes that depend on trust: free speech, civil liberties, institutional reform, ethical governance.

Critics do not need to invent counterarguments when hypocrisy supplies them ready-made.

Worse, hypocrisy gives cover to bad actors on all sides. It allows genuine abuses of power to be dismissed as “just another moral panic,” and principled defenses to be recast as self-serving shields. The result is cynicism—fertile ground for both authoritarianism and apathy.

The tragedy is that this damage is often inflicted unintentionally. The individual may see his personal failings as separate from his ideas. The public does not.

- Accountability is not censorship

One of the most dangerous confusions of our era is the collapse of all consequences into a single category called “censorship.”

They are not the same.

Censorship is the suppression of ideas, inquiry, or expression by power—especially when aimed at preventing criticism, truth-seeking, or dissent. Accountability is the response to behavior that violates ethical or professional standards, particularly when power has been abused.

A society cannot function without accountability. A society that calls all accountability “silencing” soon becomes a society where the powerful are untouchable.

This distinction matters profoundly for free speech. When advocates of free expression blur it—especially when defending themselves—they weaken the very principle they claim to protect. Free speech is not a personal immunity clause. It is a social condition that allows truth to surface.

Facing consequences for misconduct does not negate one’s right to speak. It simply affirms that speech does not place one above ethics.

FILE PHOTO: President Donald Trump speaks about early results from the presidential election in the East Room of the White House in Washington. Trump falsely claimed victory over Democratic rival Joe Biden on Wednesday with millions of votes still uncounted in a White House race that will not be decided until a handful of states complete vote-counting over the next hours or days. REUTERS/Carlos Barria/File Photo

- The tragedy of denial

Human failure, while painful, is ordinary. Denial is what transforms failure into betrayal.

There is a profound difference between saying, “I was wrong. I abused power. I caused harm,” and saying, “This is misunderstood, exaggerated, politically motivated, or irrelevant to my work.”

The first response costs pride but preserves moral coherence.

The second preserves comfort but corrodes credibility.

Denial does more than protect the self; it reenacts the very systems of silence and evasion that many critics of power claim to oppose. It teaches institutions how to look away, how to delay, how to minimize. It instructs others—especially those with less power—that truth will be inconvenient and support unreliable.

In that sense, denial is not merely personal. It is instructional.

5. Holding truth without canonizing its messenger

There is no requirement that we discard good ideas because their author failed them. But there is a responsibility to stop confusing articulation with virtue.

Ideas deserve examination on their merits. People deserve judgment on their actions. When we merge the two, we either sanctify thinkers or demonize thought—both are intellectual failures.

The more honest response is to let the ideas stand, stripped of halo and heroics, and to let the behavior stand exposed, without euphemism or excuse.

That is not cruelty. It is ethical clarity.

In the end, principles outlive their advocates. Free speech, integrity, and accountability do not belong to those who write best about them. They belong to the societies that insist on practicing them—even when doing so is uncomfortable, even when it implicates those we once admired.

Perhaps that is the final, sobering lesson: the truest test of an idea is not how eloquently it is defended, but whether it survives contact with human weakness—without being bent into an alibi for it.

Hamlet posed his existential quest for life with the famous phrase “To be or not to be, that is the question.” I woke up this morning wrestling with a somewhat different question. I wanted to go back to sleep. It was too early to get up. It was dark and cold. I did not want to leave my nice warm bed but something inside of me was in war over the question of whether I can make a difference or not in the world. Am I a fool and charlatan or a man with meaning and purpose? You might say it was my pessimist side fighting with my optimist side. It seemed more like my nihilist attitudes battling with my existentialist attitudes. Or perhaps it is my cynicism versus my somewhat subdued optimism. I will simply call these two voices “Doom and Gloom” versus “Hope and Possibilities.” The struggle between the two voices went as follows.

Hamlet posed his existential quest for life with the famous phrase “To be or not to be, that is the question.” I woke up this morning wrestling with a somewhat different question. I wanted to go back to sleep. It was too early to get up. It was dark and cold. I did not want to leave my nice warm bed but something inside of me was in war over the question of whether I can make a difference or not in the world. Am I a fool and charlatan or a man with meaning and purpose? You might say it was my pessimist side fighting with my optimist side. It seemed more like my nihilist attitudes battling with my existentialist attitudes. Or perhaps it is my cynicism versus my somewhat subdued optimism. I will simply call these two voices “Doom and Gloom” versus “Hope and Possibilities.” The struggle between the two voices went as follows.

Ladies and Gentlemen. How can you have a government of the people, by the people and for the people when it is a government of the rich by the rich and for the rich? A government of lawyers, political science majors and corporate people. An interlocking network of proponents who have a self-interest that nowhere matches the nature and interests of the general public of America.

Ladies and Gentlemen. How can you have a government of the people, by the people and for the people when it is a government of the rich by the rich and for the rich? A government of lawyers, political science majors and corporate people. An interlocking network of proponents who have a self-interest that nowhere matches the nature and interests of the general public of America.

Many of the board members in the rural counties are farmers or laborers or educators who have little or no training in the laws that they are sworn to protect. Thus, they rely heavily on the lawyers that they hire to provide advice and perceived protection from lawsuits. This renders the board members subject to the legal opinion of the lawyer which is quite often at odds to what the public wants. The boards are frequently fearful of a lawsuit (often offered by the lawyer as a possibility) and will forego making an informed decision based on evidence that is presented at the hearings.

Many of the board members in the rural counties are farmers or laborers or educators who have little or no training in the laws that they are sworn to protect. Thus, they rely heavily on the lawyers that they hire to provide advice and perceived protection from lawsuits. This renders the board members subject to the legal opinion of the lawyer which is quite often at odds to what the public wants. The boards are frequently fearful of a lawsuit (often offered by the lawyer as a possibility) and will forego making an informed decision based on evidence that is presented at the hearings.  We need less lawyers. Lawyers and lawsuits are destroying America and Democracy. We need leaders with more diversity in education. We need leaders with more ethnic diversity. We need leaders with more gender diversity. We need greater representation that reflects the demographics of America. We need less lawyers. We need more justice and we need more fairness.

We need less lawyers. Lawyers and lawsuits are destroying America and Democracy. We need leaders with more diversity in education. We need leaders with more ethnic diversity. We need leaders with more gender diversity. We need greater representation that reflects the demographics of America. We need less lawyers. We need more justice and we need more fairness.

If you think about the ideas or premises or nostrums that guide your life, you will soon notice that we have many ideas that along our journey we have adopted. The sources of these ideas are vast. Fairy tales and children’s stories give us ideas such as “A stitch in time saves nine” or the “The race does not always go to the swift” or “Those who do not plan ahead may starve in the winter.” Many of our ideas about living no come from our parents and family. My mother used to say such things as “Ignorance is bliss” and “If you give them enough rope, they will hang themselves.” My father was fond of saying “Believe nothing of what you hear and only half of what you see.” He also used to like to say, “You have nothing to fear from the dead, only the living.” These two later beliefs have guided a great deal of my life.

If you think about the ideas or premises or nostrums that guide your life, you will soon notice that we have many ideas that along our journey we have adopted. The sources of these ideas are vast. Fairy tales and children’s stories give us ideas such as “A stitch in time saves nine” or the “The race does not always go to the swift” or “Those who do not plan ahead may starve in the winter.” Many of our ideas about living no come from our parents and family. My mother used to say such things as “Ignorance is bliss” and “If you give them enough rope, they will hang themselves.” My father was fond of saying “Believe nothing of what you hear and only half of what you see.” He also used to like to say, “You have nothing to fear from the dead, only the living.” These two later beliefs have guided a great deal of my life.