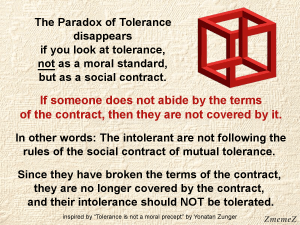

Many years ago, the famous philosopher Kark Popper created what has been called the “Paradox of Tolerance.”

Karl Popper wrote that, “if we want a tolerant society, we must be intolerant of intolerance”. This is known as the “Paradox of Tolerance”, which is the idea that a society must be intolerant of intolerance in order to maintain tolerance. As with any paradox, this is very confusing.

“Popper explained that unlimited tolerance can lead to the destruction of tolerance. He said that a tolerant society should be prepared to defend itself against intolerant views, and that the right to suppress intolerant views should be claimed if necessary. However, he also said that suppressing intolerant views through force is unwise unless they are unwilling to engage in rational argument.” —- From Search Labs | AI Overview

Recently, I came across a rather long academic article which I think supports a justification for Popper’s viewpoint. Albeit I think this article provides a more nuanced explanation for being intolerant of intolerance. I have decided to post this article since I think the times demand that we understand this perspective. I believe it is a focal point worth fighting for. You may disagree but the analogy of how Hitler took power is I think quite relevant and worth thinking about. Here in its unabridged form is the entire article. I would love to hear what you think, so please leave a comment or two.

What are the Limits of Toleration? By Tamar Lagurashvili

University of Tartu, Institute of Government and Politics, Graduate Student

Introduction

Tolerance is considered to be one of the cornerstones of modern liberal democracies, thus having acquired different implications across the countries, which ultimately leads to the ambiguity of the concept itself. In order to avoid further misunderstanding, we should clearly define what is meant in tolerance and why it is crucial not to mix this term with the words having similar connotations. Yossi Nehushtan (2007:5) offers an obvious distinction between the value-based liberal tolerance and rather neutral tolerance, which finds more similarities with indifference rather with toleration itself. Concerning its linguistic origin, author refers to the Latin word tolerabilis, which means to lift an object, clearly implying to the burden to be carried by one, who tolerates certain unacceptable behavior, act or opinion. Within this context, we should refer to Michael Sandel (1996), who differentiates liberal non-judgmental toleration from judgmental toleration. While looking closely at these concepts, we can see that in the case of former, person (tolerant) tolerates certain opinion, act or behavior without judgmental evaluation simply because he does not care or he respects others’ privacy and thus, refrains from any kinds of interference. Albeit that, refraining from interfering in other people’s private life is an integral part of modern liberalism, definition provided above does not correspond with the tenets of tolerance.

As Heywood (2015:251) rightly mentions, tolerance should be distinguished from permissiveness, indifference and indulgence, since being tolerant inherently implies to the fact that a tolerant person faces moral difficulties to put up with certain behavior or act, but does so for the sake of different reasons. Being tolerant means that a person has to impose certain restrictions on him/herself in order to avoid to openly interfere in others’ life when there is something to be disliked, disparaged or disapproved. Toleration with its basic definition can be considered as truly moral value, supporting a peaceful coexistence of the different individuals, but whether there are certain cases, where intolerance is morally/pragmatically justified is major concern of this paper.

Why do we tolerate?

Rainer Frost (2008:79-82) while touching Pierre Bayle’s Reflexive theory of Toleration, talks about three different reasons or factors, which trigger toleration among majority and minority groups. First he mentions permission conception, according to which the majority gives minority a right to live according to their customs, but toleration is possible when the “difference” of minority is contained to certain limits and does not cross the borders of private life. As an early and most vivid example of permission conception Frost names the Nantes Edict of 1598, which granted the Calvinist Protestants of France substantial rights in private as well as in public spheres.

Second way of toleration is coexistence concept, which resembles to pragmatic tolerance to be discussed bit later. In this case, avoiding conflict and paving way towards peaceful coexistence is what matters, but unlike the previous situation, here we face not the relation between the ruling majority and minority, but rather two groups wielding equal powers, thus requiring making some concessions for the sake of preventing clash of interests. If we attempt to apply this concept to real life, we can think of Somalia, who has been torn apart by three different clans ruling in three regions of Somalia, therefore hindering country’s normal development. Bearing in mind that Somalia is characterized by distinctive homogeneity (Guardian Africa: 2015), one can assume that it is not different beliefs and traditions, which impede toleration among the clans, but the economic benefits they can reap from the permanent state of conflict.

Third conception is based on the principle of respect, thus implying to the fact that toleration requires acknowledging the fact that everyone is equal and deserves equal political and legal rights.

As one can see Frost’s approach towards toleration is rather a combination of pragmatic and moral values, since it fosters cooperation between majority and minority and upholds egalitarian values. Kristie McClure (1990:361-391) puts forward John Rawls’s understanding of toleration within his notion of “ justice as fairness”, according to which toleration carries distinctively pragmatic connotation, namely the one of social conditions, which not only helped to put an end to the religious wars in Europe, but to transform religious toleration into certain form of social practice. John Locke’s work Letter Concerning Toleration is deemed to be a milestone in understanding the tenets of toleration. Locke comes from the assumption that we are all created by God and thus, our “Highest Obligation” should rest on the understanding of others’ differences for the sake of our moral obligation and love (Frost 2008). Later on Locke argues about the possible relation between the tolerant and one to be tolerated, excluding the possibility to give superiority to any church, since it will lead to persecution and monopolization of power.

One can consider that by proposing to give each and every church equal power as searching for the only true religion is futile and will exacerbate conflict between different religious groups, Locke somehow offers the coexistence concept elaborated earlier. Even though toleration is a God-given virtue, Locke still talks about its possible limits, which in his case is restricted to two kinds of groups: “A church that assumes the power of being able to excommunicate a king or that claims political and religious authority over its members…” and the atheists, as: ”They are not at all to be tolerated who deny the Being of a God” (Frost: 91-92).

Nehushtan, like Frost points out three different reasons of why people generally tolerate: tolerance as right, pragmatic tolerance and tolerance out of mercy. First he touches upon tolerance from the standpoint of rights and argues that no matter how repulsive person’s behavior or opinion can be, harm inflicted to that person cannot be justified on the grounds of personal autonomy developed by Joseph Raz . Author stresses particular importance on the pragmatic side of toleration and develops the ideas very similar to Frost with an additional insight of reciprocity and proportionality, which will be discussed later on. His third point argues that people with physical and/or mental disabilities might be exposed to more toleration than usual, regardless their repulsive behavior.

Can toleration be limited?

Tolerance with its underlying principles and applicability clearly upholds democratic values and strengthens personal autonomy, which constitutes one of the cornerstones of the liberal democracies. Albeit that tolerance is widely considered as “moral virtue”, would we go further and suggest that tolerance can be applied to each and every circumstance regardless the fact who should be tolerated? This question is examined in the works of many political scientists, including Andrew Heywood, who even though stresses importance of the political pluralism, openly talks about those political parties, which are clearly distinguished with hate speech and bigotry, thus threatening the democratic values, should not be tolerated and permitted to the political spectrum, since as author suggests: ”toleration is not granted automatically, it has to be earned” (Heywood: 256).

I would suggest that reciprocity, as a crucial feature of toleration substantively defines the nature of its applicability, which means that in certain exceptions, where we have to deal with a massive surge of intolerance, clearly undermining the democratic values and endangering the sovereignty of state, toleration should be limited. Heywood calls an example of Nazi Germany, where after the failure of Munich Putsch, Hitler and his collaborators were still allowed to pursuit their political activities legally, which ultimately led to the disastrous consequences. It seems that reciprocity plays an integral part in understanding the limitations of tolerance, so clearly expressed in the work of Nehushtan, who also talks about proportionality, which mainly focuses on the costs and benefits of limiting toleration. We could start by recalling Rawls, who suggests that:” it seems that an intolerant sect has no title to complain when it is denied an equal liberty”( Rawls 1999:190). While analyzing Rawls’s words, we can assume that those intolerant groups, which openly threaten state sovereignty and democratic values in general, should not be treated in a tolerant manner, but how can intolerance be expressed when it comes to politics? Should we ban such intolerant political parties and prevent them from entering parliament?

Should we hold a peaceful campaign, during which we will expose true information about the intolerant party’s real intentions and the scope of possible harm in case of proliferation the intolerant ideas? Deciding upon the methods of expressing intolerance is rather individual and as Nehushten suggests, is rooted in the principle of proportionality. According to the author, while working on the scope of intolerance, one should take into account the nature of intolerance and the response towards it, since if an act of intolerance takes place in parliament for example, an intolerant response should be formulated within the realm of politics and not in the private life. On the other hand, amount and nature of intolerant response should not exceed the original intolerance and what is of core importance- intolerant response should inflict minimal harm to the democratic values and human rights, because otherwise we will face counter-productivity. Fintan O’Toole (1997:346) raises another interesting question concerning the limits of tolerance based on assumption that excessive freedom of certain group might threaten collective good, thus requiring to impose certain restrictions on that group’s excessive liberty. Therefore, certain amount of intolerance towards the groups, who wield the power in order to prevent them from abusing/manipulating this power, is justified.

Nevertheless, author calls an example of Bernard Shaw’s criticism of the Christian Golden Rule (according to which we should treat others as we would like to be treated), providing the heterogeneous nature of the society, where what one person considers benign for him/herself, might be perceived as totally evil by other. Author suggests that even though there might be a society with relatively homogeneous religious beliefs, the applicability and interpretation of the customs and beliefs might considerably vary (O’Toole: 347). Therefore, we should not expect that toleration will be upheld as universal value across different societies, but what author explicitly refers to is the nature of harm inflicted by the intolerant groups, which morally and pragmatically justifies adequate intolerant response.

Conclusion

Tolerance, as one of the tenets of modern liberal thought, cannot be applied universally to every situation, without taking into account the nature of an opinion, behavior or act to be tolerated and the amount and nature of harm done to the society followed by intolerance. We can assume that intolerance is justified on the grounds of reciprocity i.e. as Heywood stated, tolerance should not be granted automatically and it requires certain effort to be excerpted by the groups demanding tolerance and proportionality, which implies that there should be balance between the original intolerance and its corresponding intolerant response. Even though tolerance constitutes a major tenet of modern liberal democratic states, where each and every individual is endowed with personal autonomy and a right of individual liberty, preventing certain individuals from infringing others’ private life, there are some exceptional cases, where intolerance can be justified. Even though individual liberty is an integral part of the democratic societies, my essay primarily focused on the limits of tolerance at the political level, where we might face much more disastrous results in case of allowing unlimited tolerance towards the intolerant groups. Having tolerant attitude is vital in pluralist societies, but when national sovereignty and democratic values are endangered due to the nature and amount of intolerance exposed to the wide public, appropriate intolerant response should be nurtured taking into account the costs and benefits of such response.

Bibliography

Frost, Rainer. “Pierre Bayle’s Reflexive Theory of Toleration.” In Toleration and Its Limits, edited by Melissa S. Williams and Jeremy Waldron. New York University Press, 2008.

Heywood, Andrew. Political Theory: An Introduction. Palgrave, 2015.

McClure, Kirstie M. Difference, Diversity and the Limits of Toleration. Sage Publication, 1990.

Nehushtan, Yossi. “The Limits of Tolerance: A Substantive-Liberal Perspective.” 2007.

O’Toole, Fintan. “The Limits of Tolerance.” By Fintal O’Toole and Lucy Beckett. Irish Province of the Society of Jesus, 1997.

Compassion is the most important of the seven virtues. Compassion is just one stroke short of love. Compassion leads to love but it takes some doing to get there. The journey involves a number of steps each predicated on a trait or behavior that is uniquely human. In this blog, I want to describe the journey to compassion and beyond to love. Each step of the journey is a commitment to humanity. If you do not care about others, you will not be interested in the journey. Compassion is the opposite of narcissism. A narcissist loves them-self. A person with compassion loves others. With a narcissist, it is “all about me.” With a compassionate person, it is “all about them.”

Compassion is the most important of the seven virtues. Compassion is just one stroke short of love. Compassion leads to love but it takes some doing to get there. The journey involves a number of steps each predicated on a trait or behavior that is uniquely human. In this blog, I want to describe the journey to compassion and beyond to love. Each step of the journey is a commitment to humanity. If you do not care about others, you will not be interested in the journey. Compassion is the opposite of narcissism. A narcissist loves them-self. A person with compassion loves others. With a narcissist, it is “all about me.” With a compassionate person, it is “all about them.” The journey starts with sympathy. We think of sympathy as “feeling sorry for someone.” It is the ability to have feelings for another person. We see another person who looks hungry or unhappy or ill and we feel some sense of remorse or regret for the other person. We might be distressed for them or we might simply be glad that we are not in their shoes. A part of us hurts or aches for the other person, but we do not identify with them on a deeper level. Our sorrow goes no further than to perhaps wonder what had befallen them to bring such misery.

The journey starts with sympathy. We think of sympathy as “feeling sorry for someone.” It is the ability to have feelings for another person. We see another person who looks hungry or unhappy or ill and we feel some sense of remorse or regret for the other person. We might be distressed for them or we might simply be glad that we are not in their shoes. A part of us hurts or aches for the other person, but we do not identify with them on a deeper level. Our sorrow goes no further than to perhaps wonder what had befallen them to bring such misery. Our next step in our journey to compassion takes understanding. We need to try to understand others and to put ourselves in their shoes. We must avoid separation and thinking that we are so different from others. We must avoid judging others. When you couple understanding with sympathy, you have taken the next step. You have now arrived at empathy. To have empathy for others, is to combine sympathy and understanding. You are sorry for those who are less well-off then you are, but you do not separate yourself from them and instead you seek to find the common ground that links you to the other person. Sympathy involves the heart. Empathy involves both the heart and the mind.

Our next step in our journey to compassion takes understanding. We need to try to understand others and to put ourselves in their shoes. We must avoid separation and thinking that we are so different from others. We must avoid judging others. When you couple understanding with sympathy, you have taken the next step. You have now arrived at empathy. To have empathy for others, is to combine sympathy and understanding. You are sorry for those who are less well-off then you are, but you do not separate yourself from them and instead you seek to find the common ground that links you to the other person. Sympathy involves the heart. Empathy involves both the heart and the mind. The next step in our journey is action. All of the empathy in the world will not make a difference if we do not take action. Empathy + Action = Compassion. Compassion is the way we make a difference to others. Jesus said “Feed my sheep.” He did not say to just take pity on them or to simply have empathy for them. Empathy by itself does not clothe the poor, feed the hungry or help the weak. We must make action and doing a part of our empathy for others. This is true compassion.

The next step in our journey is action. All of the empathy in the world will not make a difference if we do not take action. Empathy + Action = Compassion. Compassion is the way we make a difference to others. Jesus said “Feed my sheep.” He did not say to just take pity on them or to simply have empathy for them. Empathy by itself does not clothe the poor, feed the hungry or help the weak. We must make action and doing a part of our empathy for others. This is true compassion.

Bob’s actions made a great impact on me, since I had seldom gone further in my life than either waiting to be asked for help or sometimes asking others if they needed help. It would never have occurred to me to just show up and help. Perhaps, you might think that simply showing up and helping someone is going too far. However, think about yourself. Would you really ask others for help? I know I probably would not. Pitching in to help when not asked may not always be warranted but I now see it as something worth endeavoring to do more often than not.

Bob’s actions made a great impact on me, since I had seldom gone further in my life than either waiting to be asked for help or sometimes asking others if they needed help. It would never have occurred to me to just show up and help. Perhaps, you might think that simply showing up and helping someone is going too far. However, think about yourself. Would you really ask others for help? I know I probably would not. Pitching in to help when not asked may not always be warranted but I now see it as something worth endeavoring to do more often than not. Compassion is a much more useful and practical virtue for my life. I can deal with compassion and I can be more compassionate if I really aspire to. I am not sure I can be more loving. I have a hard time “loving” others whom I dislike or who do unkind things to people I do like. I more often “love” others who think and act like I do. I may be taking the easy way out, but if I can be more compassionate to others and if someday I am thought of as a compassionate person, that will be enough for me. If you are further along in your journey through life, then you should consider including love as one of your “most” important virtues. No one will be a worse person for it. For me today, compassion for others is enough of an effort.

Compassion is a much more useful and practical virtue for my life. I can deal with compassion and I can be more compassionate if I really aspire to. I am not sure I can be more loving. I have a hard time “loving” others whom I dislike or who do unkind things to people I do like. I more often “love” others who think and act like I do. I may be taking the easy way out, but if I can be more compassionate to others and if someday I am thought of as a compassionate person, that will be enough for me. If you are further along in your journey through life, then you should consider including love as one of your “most” important virtues. No one will be a worse person for it. For me today, compassion for others is enough of an effort.

At one of our mixed support group meetings, a gay man from our group challenged the rest of us, mostly the straight men to go out to a gay bar. A popular one was the Gay Nineties on Hennepin Avenue in Minneapolis. We accepted the challenge and decided that after our next support group meeting, we would all (straight and gay men) go to the Gay Nineties for a drink.

At one of our mixed support group meetings, a gay man from our group challenged the rest of us, mostly the straight men to go out to a gay bar. A popular one was the Gay Nineties on Hennepin Avenue in Minneapolis. We accepted the challenge and decided that after our next support group meeting, we would all (straight and gay men) go to the Gay Nineties for a drink.

Thus, the question arose in my mind about the difference or relationship between appreciation and gratitude. Perhaps this is like asking how many angels can dance on the head of a needle, but I thought the question deserved some reflection. Is the relationship between gratitude and appreciation similar to the relationship between tolerance and respect?

Thus, the question arose in my mind about the difference or relationship between appreciation and gratitude. Perhaps this is like asking how many angels can dance on the head of a needle, but I thought the question deserved some reflection. Is the relationship between gratitude and appreciation similar to the relationship between tolerance and respect? If you do not like to try new things, you should not travel. One of my mottos is “I have never met a food I did not like.” Karen and I eat at street vendors. We often shop locally and pick out foods that we do not even know what they are. When we were on Naxos, we found a meat market. We entered and were greeted with a variety of skinned animals hanging from hooks. There were no labels on these various creatures. We assumed they sold the meat in kilos, so we asked for a ½ kilo of this and ½ kilo of that. We decided that we would take the meats or whatever they were back to our little apartment and cook them. We figured that once we did this, we might be able to guess what we were eating. This was many years ago and I do not think we ever figured out what we were eating. The food was good and twenty-five years later we are alive and kicking. It was a great adventure. One that we have replicated many times.

If you do not like to try new things, you should not travel. One of my mottos is “I have never met a food I did not like.” Karen and I eat at street vendors. We often shop locally and pick out foods that we do not even know what they are. When we were on Naxos, we found a meat market. We entered and were greeted with a variety of skinned animals hanging from hooks. There were no labels on these various creatures. We assumed they sold the meat in kilos, so we asked for a ½ kilo of this and ½ kilo of that. We decided that we would take the meats or whatever they were back to our little apartment and cook them. We figured that once we did this, we might be able to guess what we were eating. This was many years ago and I do not think we ever figured out what we were eating. The food was good and twenty-five years later we are alive and kicking. It was a great adventure. One that we have replicated many times. I was forty years old before I had my first trip out of the USA. I had always wanted to travel and my four years in the military had not provided me the opportunity to travel. Later on, I became so busy with school and work that traveling seemed like a remote luxury. One day I was on a plane coming back from Thompson, Manitoba. (Canada does not count as foreign travel.) I had been working with a mining client that week and was now headed home. Next to me sat a young woman holding a travel guide to Spain. It was May and schools were getting out for the summer. I remarked “Are you going to Spain?” “Yes,” she replied. “Oh”, I said, “you must be very excited.” She answered somewhat petulantly, “No, I went there last summer but my parents wanted me to go again since I am studying Spanish.”

I was forty years old before I had my first trip out of the USA. I had always wanted to travel and my four years in the military had not provided me the opportunity to travel. Later on, I became so busy with school and work that traveling seemed like a remote luxury. One day I was on a plane coming back from Thompson, Manitoba. (Canada does not count as foreign travel.) I had been working with a mining client that week and was now headed home. Next to me sat a young woman holding a travel guide to Spain. It was May and schools were getting out for the summer. I remarked “Are you going to Spain?” “Yes,” she replied. “Oh”, I said, “you must be very excited.” She answered somewhat petulantly, “No, I went there last summer but my parents wanted me to go again since I am studying Spanish.” I did not say anymore to the young woman, but I thought “My, would I love to go to Spain or anyplace for that matter.” Then and there in that moment, I made up my mind. Karen and I were going to travel. We were going to see the world. When I arrived home, I shared my decision and determination with Karen. She was delighted but wondered how we would manage it. We have since been to 33 countries for a total of about 25 or more trips. We like to go to one country and see various sections of it rather than trying to see the whole of Europe or Asia in one trip. Usually we go for three weeks or so. We are very budget oriented and try to behave like pilgrims rather than like tourists. Our trips are usually a balancing act between being a pilgrim and being a tourist.

I did not say anymore to the young woman, but I thought “My, would I love to go to Spain or anyplace for that matter.” Then and there in that moment, I made up my mind. Karen and I were going to travel. We were going to see the world. When I arrived home, I shared my decision and determination with Karen. She was delighted but wondered how we would manage it. We have since been to 33 countries for a total of about 25 or more trips. We like to go to one country and see various sections of it rather than trying to see the whole of Europe or Asia in one trip. Usually we go for three weeks or so. We are very budget oriented and try to behave like pilgrims rather than like tourists. Our trips are usually a balancing act between being a pilgrim and being a tourist.